Though I never had the chance to see the program come into being, I wanted to share the proposal for teen librarians who might find all or parts useful to them. It includes the collection and program breakdown, an evaluation of our population to show why the collection and associated programming would be relevant, and links out to the teen zine programming and collections that I found being implemented at other public libraries.

If you end up using this proposal as a jumping off point for your own, please drop me a note I’d love to cheer you on and hear how it pans out!

To view in your browser, click on the hyperlinked text. To download a pdf of the proposal to your device, click the download button.

]]>

I baked two sheet cakes, one serving as the base, and the other serving as construction material. To construct Buck’s head, I stacked gradually smaller layers of cake bits that I then carved into the desired shape. The teeth are cake bits held on with toothpicks. The next step was to ice the whole thing in homemade cream cheese icing. Then I used food coloring to bring Buck to violent life, along with a winding stream out of which came a pile of gold. The gold pile I then covered in edible sparkles. The last step was to pipe on the title of the book. It wasn’t a book constructed out of edible materials (Check out Susan Mill’s artist’s book Garden Ledger for an example that’s as cool as a cucumber), but it was good enough to win the Most Creative category!

2014 was apparently the year of the cake for me. I also made the Eat Me cake for Halloween, then the guys of Pi Lambda Phi asked me to make them a Greek life cake for their 4th of July Bash. They’re not Edible Books (although the gravestone was a vague reference to Alice), but here they are for your visual consumption anyway!

What follows is the result of that investigation.

Introduction

Scholarship on the medieval period of what is now Western Europe and the United Kingdom displays a distinct preference for the mid- to late- portion of the period, neglecting history prior to 1100. This is perhaps due to the pre-1100’s comparative lack of clear archaeological and material evidence. Perhaps it is due to the period’s isolation from the Renaissance, the darling of academic imagination and the foundation for our current culture. I posit, however, that the period’s neglect is likely due the modern mind’s inability to fully adopt a “period eye” for pre-literate, temporally distant cultures like those of the early medieval period.[1] Even the way the previous sentence frames the pre-1100s as ‘pre-literate’ privileges a post-Renaissance perspective that resists acknowledging the earlier time on its own terms, preferring instead to understand it in relation to our assumption that literacy is the natural and inevitable path an oral culture must take to be sophisticated. As art theorist Michael Baxandall writes in his essay on the period eye,

one brings to the picture [or any historical materials] a mass of information and assumptions drawn from general experience. Our own culture is close enough to the Quattrocento for us to take a lot of the same things for granted and not have a strong sense of misunderstanding the pictures; we are closer to the Quattrocento mind than to the Byzantine [or early medieval], for instance. This can make it difficult to realize how much our comprehension depends on what we bring to the picture.[2]

But, as historian Brian Stock investigates in his research on the impact of literacy on oral cultures, literacy fundamentally changes the way we understand ourselves, our relationships, and construct and interact within societies.[3] We, as literate people in a literate culture, must set aside the basis of our entire worldview to glimpse the way one in an oral culture might understand reality.

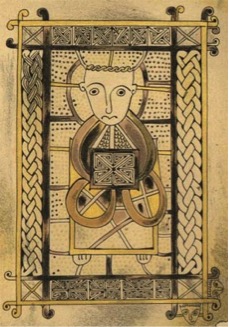

Ireland—the setting of my investigation—was an entirely oral culture until the introduction of Christianity in the early 400s C.E[4] Even with the rapid adoption of Christianity and a growing trust in the written word (upon which the Catholic Church depended for its authority), Ireland remained predominantly oral and illiterate deep into the medieval period, with only a sliver of the upper and the clerical classes boasting full literacy.[5] As such, the texts of early medieval Ireland from 600-900 C.E were primarily Christian, and the Irish scribes developed a distinctly Irish form of religious text in pocket gospels.[6] These gospel books were small, as their name suggests, diminutive in size and weight in order to accommodate a more “intimate, almost private” style of reading and to fit within the tooled and locked leather satchels, called cumdachs, that their monks wore around the neck (fig. 1).[7] Though some of these pocket gospels received additional liturgical passages and accompanying materials later, the standard pocket gospels of the 7th-10th centuries contained only the four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.[8]

Textuality in the early medieval period

Literacy goes far beyond the ability to read words and a preference for written words over aural authority.[9] In the medieval period, literacy existed within a spectrum from complete literacy to complete illiteracy, with most of those outside of complete illiteracy operating within partial literacies. When an oral culture like Ireland’s begins to incorporate the written word into its traditions, the culture is not defined by literacy or illiteracy, but by the “variety and abundance” of collaborations between the two, resulting in what Stock calls a textual culture.[10] Textuality is a more appropriately term than literacy for the early medieval Irish relationship with the written word, since it doesn’t divorce the written word from oral culture’s preference for speaking and hearing. [11] The early introduction of the written word into an oral culture results in a focus on the use of and interaction with text in certain very specific settings, not the ability to read and comprehend written ideas.[12] Instead, the book and paper take on a role in which they are representational containers of authority that serve as objects of use and facilitators of certain experiences. They do not function as texts to be read for direct textual understanding. Or, as Stock puts it, textuality focuses “not [on] what texts are, but what people do with them.”[13] For instance, the presence of a leaf of vellum at the time of an oral land transaction was sufficient to lend the agreement permanent legal authority.[14]

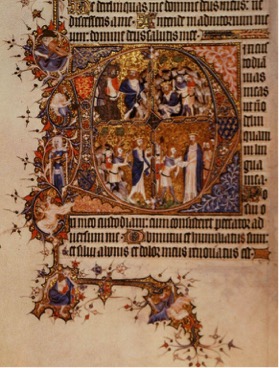

Due to the highly oral nature of the textual culture of early medieval Ireland, it is virtually guaranteed that the owners of these pocket gospels would have had the books’ contents memorized, marking the script and illumination as visual queues rather than as decorated words to be read line by line. David B. Morris adds to this supposition in his essay “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” noting that medieval church readers would have practiced repetition and purposeful memorization to make the gospels familiar and accessible for reflection, even when the text was not legible before them.[15] This is reinforced again by the continued relationship with textuality even two centuries after pocket gospels fell out of fashion; despite the significant move towards a more literate culture by this time, prayer books in the form of books of hours (fig. 2) used image and text as “memory guides for the reader…[that] operated as effective and appropriate cues for contemplation during the recitation of the familiar prayers.”[16] The function of memory in a textual-oral culture still held with the growth of literate culture.

Use of the book as an object

As mentioned previously, the containers for words—both leaves of parchment and books—held power in early medieval Ireland. This power was twofold. Firstly, they acted as a means for the Church to harness non-Christian magical practices and thinking; secondly and relatedly, they acted as objects that gave protection and, thus, deserved protection.

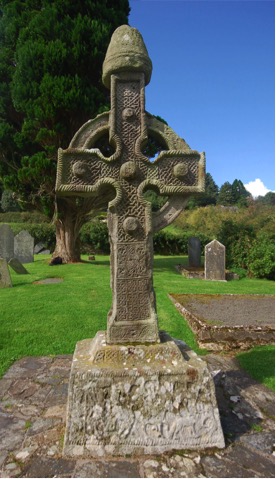

The book acted as a means of translating the Irish magic of power and miracle through the elision of local magical iconography and symbolic functioning, which was part of a larger movement of appropriation sanctioned by Pope Saint Gregory I, holder of the papal seat from 590 to 604 C.E[17] As Valerie I. J. Flint points out in her book The Rise of Magic In Early Medieval Europe, officials nurturing the introduction of Christianity into Ireland regularly borrowed and adapted non-Christian sites, objects and emotional associations with Christian ones, using everything from the placement of Christian sites to iconography on freestanding crosses to accomplish the “peaceful penetration of societies very different from their own.”[18] Like all good salespeople, the clergy framed Christianity as the newest and most effective form of magic to accomplish what the people were already seeking in their non-Christian practices. As the power of the Christian Church lies in its canonical scripture, it follows that it would have a vested interest in impregnating the Bible and other Christian texts with mystical power. Reverence for the power of books would be a natural progression in a textual culture that developed out of a religious context. With books holding the divine magic of the word of God, it follows that books themselves would be revered as magical objects, and the clergy would themselves be honored as those who could provide access to and dispense this power.

In order to further the effort to align Christian texts with non-Christian mysticism, illuminators and those executing other Christian crafts used the local aesthetic vocabulary. Flint notes that

[a]s impressive memories of non-Christian hanging sacrifices, special stones and woods, omens, and supernatural means of healing are carried vividly and carefully into the monuments[, ivories, metalwork, and illuminated manuscripts] proclaiming Christianized and supernatural power at the new shrines then, so too, on a rather smaller scale, are echoes of other forms of supernatural practice, such as amuletic rings and knots, weaving, and binding. All of these, obviously, are to be rendered subordinate to the new ways of invoking the supernatural; yet also they are still to form part of it, where this is possible.[19]

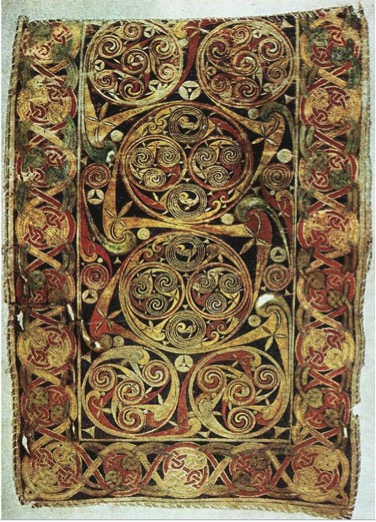

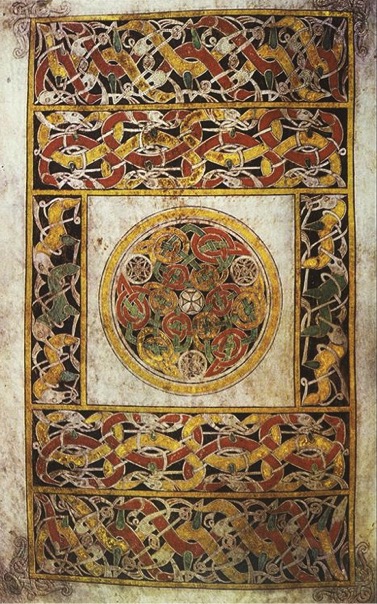

Thus, it is unsurprising that the monkish illuminators would have used the mesmerizing iconography known to the Irish people. The Book of Durrow’s carpet pages (figs. 3 and 4), some of the most famous pages from any of the pocket gospels, provide the perfect opportunity to observe the direct parallels drawn between both carving and metalworking and illumination. Observe how the interlacing, abstracted animals and triskeles in the Book of Durrow pages, the north high cross at Ahenny (figs. 5 and 6) and the Tara brooch (figs. 7 and 8) match so closely. They are drawn directly from the pre-existing Insular art so recognizable to and standardized by the people of Ireland. This iconography would have been associated with status and protection.[20]

The book provided protection and was something that needed protecting. Since the Church had effectively used the attitude of a textual culture towards books to its advantage, the people associated them with magic and all of its associated power. The protective quality lent to these pocket gospels was so enduring that even into the 17th century, the Irish public still viewed them as powerful protective objects; a farmer went so far as to immerse a section in his cattle’s drinking water to cure them of illness.[21] Within the medieval period, these pocket gospels were seen as so protective that clans used them in battle as a talisman—known as a cathach or battle book—for victory.[22] One cathach in particular boasts an infamous history. The Cathach of St. Columba—also known as Colm Cille—was used in battle by the Donegal clan until the 11th century (fig. 9).[23] In fact, the sanctity of texts was regarded so highly that this book inspired a battle of its own prior to the clan’s ownership. St. Finnian lent the book to Colm Cille, who created an unauthorized copy of the text, which Colm Cille refused to give back to St. Finnian. A failed arbitration between the parties led to the battle of Cul Dremhne in 561 C.E.[24]

These pocket gospels required protection of their own in turn, in order to preserve the positive magic of God from the influence of evil.[25] Externally, the books were guarded by cumdachs. These satchels—or sometimes altars—had locks to protect from theft, as is evident from one of the only extant medieval satchels (fig. 10), which held the Book of Armagh. The satchel also exhibits the iconography already seen in the north high cross at Ahenny and the carpet pages from the Book of Durrow. The interlacing that brings to mind wattle fencing is likely the most associated with protection and containment. This type of hurdle was used to contain livestock and to demarcate land ownership or purposes, so it follows that it was also meant to serve as a containment or binding of the divine word to the pages of the book and to act as a deterrent to evil forces that might enter and corrupt it.[26] These weavings only bound the exterior flap of the satchel, but also portions of the Tara brooch (fig. 8) and the internal illuminations in many of the pocket gospels (fig. 1, 3 and 4).

Use of the book as a facilitator of experience

The book, as is suggested by the protective ornament, served as the incarnation of and access to the Christianized magic of the divine. Eleventh through twelfth century scholar and clergyman Hugh St. Victor cements this idea in his codification of principles around reading—developing prior to and during his time—when he writes,

The divine Wisdom, which the Father has uttered out of his heart, invisible in Itself, is recognized through creatures and in them. From this is most surely gathered how profound is the understanding to be sought in the Sacred Writings, in which we come through the word to a concept, through the concept to a thing, through the thing to its idea, and through its idea arrive at Truth.[27]

It is this divine truth manifested within and made accessible through Christian texts that held the purpose behind reading for early medieval monks in Ireland. Reading allowed clergy to seek, and potentially find, the supreme truth they sought through a prescribed process frequently referred to as the Lectio Divina and referred to in Hugh’s text on reading as the ‘four steps’ (which were, in fact, numbering five).[28] Hugh’s version of the Lection Divina follows this order: (1) study or reading for understanding; (2) meditation for counsel; (3) prayer to make petition; (4) performance, which is the process of seeking the truth; and, finally and nearly impossible to achieve, (5) contemplation upon the previous four steps for the finding of truth. The steps were theoretically succeeding, but required frequent regression to earlier steps to begin the process over in order to better achieve the step of finding divine truth.[29]

This process termed ‘reading’ has very little to do with reading as we now understand it, however. It was not a literal reading of the words on the page; instead, early medieval ‘reading’ represented a full-body reflective process embedded in the oral culture’s mentality that “you know what you can recall.”[30] This attitude results in religious books for a textual culture, books serving as a “written series of things readied for oral recall” to achieve intellectual and spiritual improvement.[31] It is also this attitude of textual culture that implies that the pages of the pocket gospels would likely have served more as cues for familiar, oft-visited memory paths than lines literally reread repeatedly.[32] The memory-focused approach allowed each recitation to follow the path of the Lectio Divina—a reader was not caught up in the process of reading, but in the process of reflection on the words being ‘read.’[33]

The idea of the book as a tools rather than as reading material actually fits comfortably within the progression of Western, Mediterranean-oriented culture both before and after the early medieval period. In the Roman tradition—as described by archaeologist Bettina Bergmann—memory training involved building an argument or recitation by building a mental home in which one travelled linearly past paintings depicting the argument as it proceeded.[34] Gospel books, thus, act as a physical manifestation of this guide in the early medieval period, whose Christian education long drew from Classical education and traditions.[35] The late medieval and early Renaissance periods also show a continuation of this progression in the form of books of hours, mentioned previously. These prayer books served to bring the reader closer to the truth contained within God’s word through the same meditative process seen in the Lectio Divina of the early medieval period, though for laypeople rather than for clergy.[36]

The experience facilitated by memorization and ‘reading’ in the Lectio Divina approach—as argued by both Hugh St. Victor and David B. Morris—promises not just spiritual health, but also bodily health.[37] During the early medieval period, a distinction was not drawn between the two; thus, to cure one’s spiritual ailments through the Lectio Divina process of accessing God’s healing truth, one also cures bodily ailments, thought to be manifestations of spiritual evil or weakness.[38] Hugh best phrases the dual benefits of Lectio Divina and the meditation encompassed within it when he writes,

[t]he start of learning, thus, lies in reading, but its consummation lies in meditation; which if any man will learn to love it very intimately and will despite to be engaged very upon it, renders his life pleasant indeed, and provides the greatest consolation to him in his trials. This especially it is which takes the soul away from the noise of earthly business and makes it have even in this life a kind of foretaste of the sweetness of the eternal quiet.[39]

Meditation removes the reader from the weaknesses of the body to return it to the perfection of God’s original creation. Once the reader returns to the material word after basking in the light of God’s truth, he is meant to return to his body, healed.

Conclusion

The book, in the form of pocket gospels in early medieval textual Ireland, served as an object of protection and as a means of accessing divinely blessed states of wellbeing. It is the culture of early medieval Ireland that allowed these functions to develop, thanks to the still fluctuating cultural relationship with literacy and non-Christian magic. Christian texts gained their power because they became bridges, a bridge between the Christian and non-Christian; a bridge between the oral and literate culture; and a bridge between divine power and humankind.

Figures

Bibliography

Bäuml, Franz H. “Varieties and Consequences of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy.” Speculum 55.2 (1980): 237-265.

Baxandall, Michael. “The Period Eye.” Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988.

Bergmann, Bettina. “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii.” The Art Bulletin 76.2 (1994): 225-256.

“Book of Durrow.” Pangur’s Bookshelf. 24 Aug. 2014.

“Cathach of St. Columba.” Encyclopedia of Irish and Celtic Art.

Cunningham, Lawrence S. and Keith J. Egan. Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition. New York: Paulist Press, 1996.

Cusack, Margaret Anne. “Mission of St. Palladius.” An Illustrated History of Ireland.

Flint, Valerie I. J. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991.

Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

“Hurdles & Fencing.” The Dorset Woodsman. 2016.

McGurk, Patrick. “Irish Pocket Gospel Book.” Sacris Erudiri 8 (1956): 249-269.

Morris, David B. “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 (Summer 2006): 539-561.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Stock, Brian. After Augustine: The Meditative Reader and The Text. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Stock, Brian. The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983.

Stock, Brian. Listening for The Text: On The Uses of The Past. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

Stocks, Bronwyn. “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours.” Word & Image 32.1 (2007): 16-24.

“The Cathach / The Psalter of St Columba.” Royal Irish Academy. 12 Sept. 2016.

Westwell, Chanry. “Put It In Your Pocket.” Medieval Manuscripts Blog. December 18, 2013.

Wiener, James. “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art.” Ancient History Et Cetera. 30 Oct. 2014.

Yvard, Catherine. “Pocket Books.” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[1] The period eye is a tool for scholars to construct—using contemporary documentation and evidence—the context and cultural signifiers of a time, enabling a fuller acknowledgement of and negotiating around modern biases and assumptions; Michael Baxandall, “The Period Eye,” Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988), 29-108.

[2] Baxandall, “The Period Eye,” 35.

[3] Stock investigates this idea throughout three of his books; Brian Stock, Listening for the Text: On The Uses of The Past (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990); Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983); and Brian Stock, After Augustine: The Meditative Reader and The Text, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

[4] In 431 C.E., Pope Celestine commissioned Palladius to mister to the Irish believing in Christ, suggesting that Christianity had established itself sufficiently to garner attention from the clergy in the decades before 430 C.E.; Margaret Anne Cusack, “Mission of St. Palladius,” An Illustrated History of Ireland.

[5] Stock, Listening for the Text, 142; Franz H. Bäuml, “Varieties and Consequences of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy,” Speculum 55.2 1980: 238.

[6] While the pocket gospel tradition remains strong through the early 12th century, I chose the period from 600-900 C.E. because the 600s marks the earliest known examples of this type of book and the 900s starts the period in which scribes began inserting additions and developing a more Anglo-Saxon style of illumination; Chanry Westwell, “Put It In Your Pocket,” Medieval Manuscripts Blog, December 18, 2013; Catherine Yvard, “Pocket Books,” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[7] Patrick McGurk, “The Irish Pocket Gospel Book,” Sacris Erudiri 8 1956: 250.

[8] Catherine Yvard, “Pocket Books,” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[9] Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World (New York: Routledge, 2002), 5-6.

[10] Stock, Implications of Literacy, 42.

[11] Ibid., 145.

[12] Ibid., 143-144.

[13] Ibid., 144.

[14] Ibid., 144.

[15] David B. Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 2006: 551.

[16] Bronwyn Stocks, “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours,” Word & Image 32.1 2007: 16.

[17] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 256.

[18] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 4 and 254-257.

[19] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 260-261.

[20] James Wiener, “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art,” Ancient History Et Cetera, 30 Oct. 2014.

[21] “Book of Durrow,” Pangur’s Bookshelf, 24 Aug. 2014.

[22] “Cathach of St. Columba,” Encyclopedia of Irish and Celtic Art.

[23] “The Cathach / The Psalter of St Columba,” Royal Irish Academy, 12 Sept. 2016.

[24] Ibid.

[25] James Wiener, “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art,” Ancient History Et Cetera, 30 Oct. 2014.

[26] “Hurdles & Fencing,” The Dorset Woodsman, 2016.

[27] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, trans. Jerome Taylor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 122.

[28] Originating in the writings of Saint Benedict in the 6th century, Lectio Divina traditionally proceeded through a fourfold process: (1) reading; (2) meditation; (3) prayer; and (4) contemplation. Lawrence S. Cunningham and Keith J. Egan, Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition (New York: Paulist Press, 1996), 38.

[29] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, 132-133.

[30] Ibid., 93-94; David B. Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 2006: 542; Ong, Orality and Literacy, 3.

[31] Ong, Orality and Literacy, 121.

[32] Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” 551.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Bettina Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii.” The Art Bulletin 76.2 1994: 225.

[35] Stock, Implication of Literacy, 16.

[36] Stocks, “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours”: 16.

[37] Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” 551.

[38] Ibid., 551-552.

[39] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, 92-93.

N.B. All images reproduced under the principle of Fair Use.

]]>Title: La reforma agraria es la ley fundamental de la revolucion

Author: Ruz, Raúl Castro, 1930-

Published: [Havana] : Seccion de impresion, Capitolio Nacional, 1959

Format: Book

Call Number: S477 .C8 C37[1]

This transcription of the speech given by Commandant Raúl Castro Ruz, Chief of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, in Spanish before Cuba’s First National Forum on the Law of Agrarian Reform on 29 June 1959 displays the country’s new nationalism. This governmental pride includes definitions; the government pursues agrarian reform against poverty, but is ostensibly not communist, anti-communist, Catholic, or against America.[2] Since the speech took place three days after the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista, this self-identification justifies the government’s existence and shows support for their population, primarily non-landowning farmers.

The physical document reinforces this pride. While the sun-bleached, foxed and mimeographed front sheet—formerly blue and with rust stains from the staples holding the sheets together—presents a mundane face, the colophon proclaims the printer’s nationalism through use of the first copies of the stenciled paper “Jaguar,” which was manufactured in Cuba by Cuban workers.[3] The technical staff of the National Capital chose this paper, measuring 33×21 cm, over foreign alternatives, despite inconsistent weight. The staff produced the document quickly for circulation, as well, since they fed several off-centered sheets through the typewriter, typed corrections overtop of mistakes, and inserted missing words above slashed indicators.[4]

Louis A. Pérez, former owner, maintained the document, but for tears to the head of the last four leaves, the last tear extending to the first line of text. Though quickly produced and partially damaged, special collections would value this document, as it represents a pivotal moment in Cuban history and printed propaganda, often lost to history. UNC specifically benefits from its inclusion, since it complements RBC’s active Latin American collecting area and Spanish language collections.[5]

[1] The format for the heading I found in UNC’s library catalogue and reconfirmed through observation; “La Reforma Agraria es la Ley Fundamental de la Revolucion,” UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries Catalog.

[2] Raúl Castro Ruz, La Reforma Agraria es la Ley Fundamental de la Revolucion (Capitolio Nacional [Havana]: Seccion De Impresion, 1959), 26-7; translations my own.

[3] Ibid. 30.

[4] The correction typed overtop of words only occasionally appear to have employed whiteout before typing overtop; for examples of the types of corrections, see pages 6, 17 and 23.

[5] Rare Book Collection, “Collection Development Policy of the UNC-Chapel Hill Rare Book Collection.”

]]>The Rare Book Collection held the opening reception of Lyric Impressions: Wordsworth in the Long Nineteenth Century on 22 February, followed by a lecture from Professor Duncan Wu of Georgetown University entitled “Wordsworthian Carnage.” As the title suggests, the exhibition situates Wordsworth in a larger historical context. Less overt exhibition objectives included publicly establishing RBC’s scholarly authority in this area and thanking current donors while eliciting future ones.

The contextualizing objective allowed curator Elizabeth Ott to draw on their repository of eighteenth through twentieth century British Romantic materials. The items evoked resonance and wonder for visitors. Those versed in Wordsworth ogled marvels, like the first edition of Lyric Ballads (1798). Others found resonance in Wordsworth’s broader cultural influences. I became arrested by The Prelude: An Autobiographical Poem, 1799-1805 printed by the Doves Press in 1915, displaying Wordsworth’s relevance in posthumous aesthetics, here the Arts & Crafts movement.[1]

The exhibition materials, their interpretive text, and the opening lecture by a foremost scholar on Wordsworth allowed the RBC to highlight its strength on the period generally and its collection specifically. This underlines RBC’s dedication to engaging with its collection publicly and in scholarly discourse, fulfilling the exhibition’s scholarly objective.

Donors ensure the RBC’s growth and potential for scholarship. In this instance, Mark L. Reed, III, emeritus professor of humanities at UNC, donated the core of the Wordsworth collection that inspired the exhibition. Lyric Impressions fulfilled the objective of thanking current donors. The attention given both to the materials and to Professor Reed for his 1,700-volume gift encouraged the interest of future donors, who may be assured that their materials and involvement will remain publicly relevant.

In terms of size, the exhibition was approachable, and its scope targeted Wordsworth and the long nineteenth century, from the French Revolution to the First World War. Ott selected an array of 140 materials from the Wordsworth collection, from first editions to picturesque mini calendars. While the physical layout encouraged meandering, a glance at the exhibition reader’s table of contents clarified the cases’ intended order. The interpretive text for each object and case connected the relevance to Wordsworth and contemporaneous changes. The primary weakness of the exhibition, however, lay in the exhibition plaques’ legibility; font size, visual density of the text, and lighting compromised the reading experience.[2] While the descriptive text suited a scholarly audience, legibility issues challenged older audiences, demanding the use of readers.

Lyric Impressions epitomizes a specialized and documentary approach to collection development and its presentation to the public. These practices common to academic rare book collections make the RBC appealing to donors and visitors alike.

[1] For more on resonance and wonder in exhibition presentation, see Stephen Greenblatt, “Resonance and Wonder,” in Ivan Karp, Exhibiting Cultures: the Poetics and Politics of Museum Display (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 41–56.

[2] In approaching evaluation of the exhibition viewing, I drew upon the standards laid out in “Leab Exhibition Awards Evaluation Criteria,” RBMS Rare Books Manuscripts Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries.

N.B. The image of the exhibition poster included at the beginning of this post was drawn from UNC’s previous exhibits website under the purview of Fair Use.

]]>In order to follow along with the transcript or to view the presentation alone, please visit https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/10BDUcSyLaWe8gZDA_1c77mo2cquhUxnaIVVbYKVs2Eo/edit?usp=sharing.

]]>The app provides a vast array of aesthetically cohesive templates, but they’re not terrible customizable. In the ‘Design’ tab, you can alter the inspiration for the automatic selection of the most appropriate color scheme (helpful if all of your images are already color cooperative), the color scheme, font style & size and animation emphasis (AKA text block and media size). In the ‘Layout’ tab, you can select three options for how the flow proceeds.

From the Sway homepage, I chose to start the presentation from a document I had saved to my computer. This generated an automatic template that segmented the text and images into relatively intuitive chunks and headings. It intuited the headings just from the bolded caps lines that I had in the document as placeholders. Anything placed in a table cell (my shorthand for Tip & Tricks boxes) it turns into images. This is a nice idea, but if you have linked material, it’s no longer accessible in the image and needs to be reformatted as text. The media additions were relatively intuitive and responsive, and embedding on Sway is by far the easiest embed process of any platform I’ve worked with.

With the limited levels of customizability in exchange for pre-curated designs, Sway operates as PowerPoint for those who are more comfortable with a WordPress visual editor approach to user experience; there’s a button for all the functions, and there aren’t too many buttons.

This app works best for small presentations that aren’t terribly text heavy, as well. The assignment required us to select a focused topic and write up a multimedia mini blog post (500-1000 words). Even with the mix of media and the limited word count, it still proved challenging to keep the text dynamic and visually pacing. If coordinated with a formal verbal presentation, I could see this app as a major time saver and means of cutting down on design stress.

It strikes me that the main virtue of Sway is that, once you get over the relatively small learning hump, it’s a quick and dirty means of creating a low-input, low-stress presentation that looks like you put more effort in than you did.

Take a look:

To see how all of the individual Sway presentations embed into one presentation as a compilation, check out the class Sway presentation that our professor Denise Anthony put together:

]]>The presentation is embedded below. To see the accompanying speaker notes, click on the gear icon and select ‘Open speaker notes.’

The reading assigned by Dr Gibson for this class session:

- Mandel, L. H. (2010). Geographic information systems: tools for displaying in-library use data. Information Technology and Libraries, 29(1), 47.

- LeRoux, C. J. (2009, September). Social and Community Informatics Past, Present, & Future: An Historic Overview. Speech presented at the 10th Annual DIS Conference. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.551.1067&rep=rep1&type=pdf

The readings I assigned for this class session:

- Meeks, E. (2012, October 1). Modeling Networks and Scholarship with ORBIS. Retrieved May 14, 2016, from http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-3/modeling-networks-and-scholarship-with-orbis-by-elijah-meeks-and-karl-grossner/.

- Scheidel, W., & Meeks, E. (2013). ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World. Retrieved May 14, 2016, from http://orbis.stanford.edu/. Think about how the ORBIS project might be scaled down for a library setting that would be compelling for libraries (and their boards).

- Weingart, S. (2014, April 28). Principles of Information Visualization. Retrieved May 14, 2016, from http://www.themacroscope.org/?page_id=469. Focus on paragraphs 1-55; 83-92.

- Nessa, S. (2013, June 13). Visual Literacy in an Age of Data. Retrieved May 14, 2016, from https://source.opennews.org/en-US/learning/visual-literacy-age-data/. Focus on the section titled ‘What is Visual Literacy?’

The book arts present a fascinating mix of scholarship and craft in which artists and artisans both expand on traditional techniques and engineer solutions to novel problems. Humans display a persistent need to document their ideas in story-telling form: cave paintings, clay tablets, papyri scrolls, codices, artists’ books, and e-books. The evolution of these formats tracks the accumulated knowledge that book artists still employ today, explaining why scholarship is integral to the craft of book arts. As such, a core collection for book artists must include everything from encyclopedias to broad histories to technical texts in the format of videos, written tutorials, history books, catalogues of online resources, sample books, and binding equipment. This collection is intended to form a cohesive presentation of the resources and equipment necessary for a broad sampling of book artists, providing an accessible starting point for students and practitioners in their own research and collection building.

My senior year of undergrad, a library coworker introduced me to the book arts program at Wellesley College. It is composed of the ideal trifecta of departments: studio book arts, conservation and special collections. Katherine Ruffin heads the Book Arts Lab, Emily Bell the Conservation Lab, and Ruth Rogers & Mariana Oler the Special Collections. In the Book Arts Lab, we learned about equipment safety, typesetting and printing on Vandercook presses, historic and modern bindings, papermaking, and a general history of the book. Emily provided support for individual students on more in-depth projects beyond the scope of the introductory course. Special Collections provided a hands-on look at the implementation of book arts from the pre-print books to contemporary conceptual artists’ books. Over the course of this class, Katherine, Emily, Ruth and Mariana provided us with a number of essential resources, many of which I still seek out today. Unfortunately, the syllabus and handouts wandered off since graduation, so I lost track of the majority of those sources. After speaking with other practitioners, I’ve realized that many others also struggle to keep those lists in a safe, consistent form. My hope is that, because the collection I’ve put together is stored on a publicly accessible board on Pinterest, the Books Artists’ Core Collection will act as a practical means of tracking essential resources for book artists.

Book Arts & Book Artists

As I first learned from Wellesley’s Intro to Book Arts and have continued to experience, book artists and book historians display a considerable willingness to share their knowledge. This, I believe, is indicative of the apprenticeship nature of the book arts. While apprenticeship is a wonderful and necessary system of knowledge sharing, it complicates efforts at creating an authoritative collection of sources for the diverse artists that populate the discipline.

The book arts cover many branches of artistic creation, all of which are employed in the production of both artistic and functional materials. These branches include papermaking, letterpress printing, printmaking, calligraphy, illumination, binding, and digital media. Regional histories of the book, primarily divided into Western, Asian, and Middle Eastern, form the trunk for those branches.[1] Artists’ preference for either historic, traditional book arts or for novel book forms and practices form the roots. The ‘tree’ of book arts is far reaching and various. To create a core collection broad and deep enough to feed that tree, I chose to house the digital collection and catalogue on Pinterest.

Why Pinterest?

Pinterest is a global social media site that performs as a community “bookmarking tool that helps [its users] discover and save creative ideas.”[2] Pinners (users) can create boards on whatever topic they wish and pin relevant items of interest from the Internet to that board. By clicking the pin, users are directed back to the pin’s webpage of origin.[3] The real beauty of Pinterest, though, lies in its varied access points to the site’s communal knowledge gathering. Pinterest boasts several different searching options to engage with that knowledge community: (1) a keyword search function that seeks out pins either on your own boards or across the whole of Pinterest, (2) a browsing function that allows pinners to see pins related to a particular pin, (3) a browsing function that allows pinners to see boards related to a particular board, (4) a browsing function that allows pinners to see other boards on which a particular pin is pinned, and (5) a browsing function that allows pinners to see what else from a particular site has been pinned to Pinterest.

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

This sort of searching and browsing turns Pinterest into a highly linked catalogue and thesaurus. One pin can create an entire network of related items, which means that the Book Artists’ Core Collection acts as a jumping off point for practitioners to research more in-depth projects. For example, if an artist wishes to create a medieval book of hours, she can find the items in the core collection on parchment and papermaking, medieval bindings, paleography of the period, and illumination styles from various regions. Then once she determines the period and region she wishes to emulate, say a 14th century English binding, the artist can use those pins from the collection to seek out related items to provide further resources that are too specialized for the Core Collection, such as the saints that would have been significant to the region at the time or the plants and scenes most popularly illuminated, etc. Pinterest functions as an ideal means of creating a collection not limited by individual holdings, and thus not limiting those using the collection.

The Book Artists’ Core Collection board is also publicly available to anyone online with access to Pinterest. Having this core collection catalogue generally available helps combat the knowledge loss from misplaced handouts and course syllabi. Also, by storing the catalogue on Pinterest, users of the collection have not only easy browsing options, but also a simple means of accessing the online resources, such as the YouTube tutorials and samples of digital artists’ books. The major drawback of Pinterest as a platform for the collection lies in its lack of tagging. While I listed the subject headings in the description boxes for each pin, Pinterest has no function to search the collection by subject heading within the board, meaning that users have to scroll through the pins to locate items that might be of interest. While this is a major disadvantage, I felt that it was negligible compared to the advantages of the platform. Firstly, the collection is small enough that scrolling through is not too onerous, and two, it requires users to become familiar with the collection as a whole, thus introducing them to connections between resources that they might otherwise have missed.

The Collecting Process

My collecting process began with seeking out my old handouts and syllabus from Wellesley’s Intro to Book Arts course. Failing to locate those, I turned to the authorities in the discipline to orient me: the Center for the Book at the University of Iowa, the Book Arts Program at the University of Alabama, and the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia. Iowa and Alabama are renowned for the strength of their book arts studio programs and the Rare Book School (RBS) is internationally respected for its instruction in the study of the book arts and the history of the book. Like Wellesley College, the studio programs’ websites listed only course options, not course syllabi. From their course listings, I formed the structure of the Book Artists’ Core Collection:

- General History

- Papermaking

- Printing

- Calligraphy & Illumination

- Binding

- Digital Lab

- Equipment

My source for the resources under of each of these subject headings came almost exclusively from the RBS’s curriculum website, which does provide syllabi online for every course. I’m confident in the efficacy of these headings, since they are used as guiding themes by the Center for the Book, the Book Arts Program and the RBS, as well as my Wellesley course. I provide a breakdown of each subject heading in the sections below. Katherine and several other regional book artists also contributed noteworthy resources to supplement the thorough reading lists from the RBS. Though I depended primarily on RBS for hardcopy materials and select databases, the collection is still well rounded; the RBS hosts an extensive faculty of international scholars and experts in the study of book arts. By selecting a large cross-section of resources from the syllabi in all relevant subject areas, the Book Artists’ Core Collection remains broad and balanced. The tutorial videos channels from YouTube I selected from my own familiarity with the skills displayed, confirmed in their authority by aligning with the instructions given by well-respected authors in print. The equipment I chose from the most commonly needed items in a book arts studio that are not finite, and therefore reusable by multiple patrons for an indefinite period of time.

I chose not to emphasize the library science-oriented portion of the study of book arts because, while scholarship is necessary to the practice of book artists, information about collections management and analytical bibliography generally do not hold much relevance. I also didn’t include individual artists books in the collection because of the cost per book and because that sort of collecting is more within the sphere of special collections. The sole exception to this rule is Karen Hanmer’s Biblio Tech: Reverse Engineering Historical & Modern Binding Structures with a focus on board attachment (2013), which is meant as a teaching tool and provides such an array of binding structures that it is worth the investment. I instead included catalogues of artists’ books, ones that described binding styles, as well as more standard artwork metadata.

In the sections below elaborating on the subject headings, I have only included highlights from the collection to illustrate the sort of resources under that heading. While the collection is small enough to browse, it still contains 240+ items, most of which are fall under more than one heading due to the interdisciplinary nature of book arts. Therefore, listing them all under each heading would test any reader’s patience. Instead, I request that you visit the catalogue on Pinterest to examine the entirety of the collection.

General History

General history primarily contains the items that describe the historical development and evolution of various techniques in the book arts. For instance, Edo & Paris recounts the realities and depictions of early modern urban life and the state drawn from illustrated books from the period, allowing artists to see which styles were appropriate in which contexts and how they interacted with the codex form.[4]

This section also contains general knowledge, such as dictionaries and encyclopedias. I included these in this section because terms often developed and expanded over time, thus history can be read from the definition of terms. One example in the collection is the ABC of bookbinding: a unique glossary with over 700 illustrations for collectors and librarians. Though oriented towards library professionals and collectors, identification of terms from both text and image is key for book artists, particularly those new to the discipline.[5]

Papermaking

Papermaking, parchment making, and paper selection are all included under the Papermaking subject heading. This section includes instruction manuals, histories of writing surfaces and paper sample books. Japanese Papermaking: Traditions, Tools, and Techniques is representative of both the history texts and instruction manuals, since it goes through the historical techniques and their contexts in Japan. Sample books of both textblock and cover material are necessary to a core collection because it can be prohibitively expensive for individual artists to order sample books for each type of paper in which she’s interested. For instance, one company might have five lines of decorative papers, each of which have a sample book. Without actually interacting with the material, it can prove challenging for artists to select the appropriate papers just based on descriptions and a picture. Fine Papers at the Oxford University Press is representative of sample books, though it comes in a more traditional book form than many others.[6]

Printing

This subject heading includes both typography and illustrative printing. For the typography section of Printing, the collection primarily covers the development and history of typefaces and type design. For illustrative printing, the collection focuses on the identification of different kinds of printing methods and the use of illustrations in texts and ephemera. The printing section does not cover much instruction on the technical process of either branch of printing, since the knowledge needed changes for each press and since so many types of illustrative printing exist (e.g. drypoint and wood block). American Wood Type, 1828-1900 is representative of the typography portion of Printing. It follows the development, creation, dissemination and use of wood type in early-modern America. Another sort of typography resource includes those like graphic designer Marian Bantjes’ Ted Talk, in which Bantjes describes how graphic design and her individual style influences the way she depicts text.[7] The Picture Postcard & Its Origins is representative the ephemera section of illustrative printing, providing reference images for artists looking to create images of their own.[8]

Calligraphy & Illumination

Calligraphy & Illumination I incorporated together as a subject heading because they share many of the same tools and techniques and are often addressed together in book arts literature. Paleography, though, is the primary domain of Calligraphy, just as manuscript illumination is the primary domain of Illumination. Palaeography, 1500-1800: A Practical Online Tutorial from the National Archives represents the former and is one of several online tutorials that provide history, identification and execution as their focus.[9] Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art represents the latter, as well as the former, displaying specimens from books of hours, the most common and highly illuminated genre extant from the medieval period.[10]

Binding

Binding, alongside Papermaking, serves as the most significant contribution to book arts technical skills offered by this collection. This subject covers both the history of binding styles and tutorials on replicating binding structures. Historically, much scholarship has been dedicated to analyzing the covers of books; Twelve Centuries of Bookbinding, 400-1600 is one of these texts that couches cover analysis within historical context.[11] The historical and technical is combined in Bookbinding Materials And Techniques, 1700-1920, in which the author couches technical innovations in its historical context.[12]

For book structures, both tutorials and models are essential. To provide models, I included Karen Hanmer’s Biblio Tech binding set, as mentioned in the section on The Collection Process.[13] Making Handmade Books: 100 Bindings, Structures & Forms provides instruction for various binding structures, both traditional and modern.[14]

Artists’ books also fall within this subject heading. As a form begun in the twentieth century, the discipline is still testing the bounds of what it means to create an ‘artist’s book.’ As Ruth phrased it when explaining her collecting process, “if it tells an engaging story in a novel way and it fits on the Special Collection’s shelves, it’s an artist’s book by my definition.” Essentially, though, an artist’s book is a work of art that interacts somehow with the storytelling aspect of a book structure. Johanna Drucker, in The Century of Artists’ Books, provides the most engaging overview of the artist’s book, situating it historically and stylistically, as well as examining its conceptualization.[15]

Digital Lab

The Digital Lab resources are the least developed part of the core collection. Because this is still such a new field in the grand scheme of book arts, a critical volume of resources has not yet developed. I included critical and technical resources, as well as some exhibition catalogues, to provide basic context, skills and examples of how artists are beginning to incorporate the digital into their practice. For the critical, I included The Abominable Digital Artists’ Book: Myth or Reality? by Esmée de Heer.[16] She defines the artist’s book and discusses the current status and potential future of digital technology in their creation. For skills acquisition, I included the Tate’s workshop on Transforming Artists Books, which links to the workshop reflections on skill sets and forms.[17] The best exhibition catalogue I encountered was Non-visible and Intangible, hosted by Hampshire College from 7-16 November 2012.[18] It shows the various stages at which digital technologies might integrate with more traditional forms, as well as how to make the digital form interactive in unexpected ways.

Equipment

As mentioned previously, I chose the equipment from personal observation of the most necessary items in a book artist’s toolbox that are not finite. Finite items—like paper, thread, and ink supplies—belong to the realm of art cages or studios rather than libraries. As such, the Book Artists’ Core Collection includes items like a travel kit of binding equipment, a sewing frame and a collapsible punching trough. These items can be repeatedly checked out by any number of users to supplement their own collections or help them get a feel for which styles or brands of equipment they most require.

[1] This particular breakdown of book arts was informed by the curriculum at both the University of Iowa Center for the Book and theBook Arts Program at University of Alabama.

[2] “Press.” About Pinterest. 2015.

[3] For more about using Pinterest, see the website’s promotional video.

[4] Henry D. Smith, II. “The History of the Book in Edo and Paris” in Edo and Paris: Urban Life and the State in the Early Modern Era. Edited by James L. McClain et al. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994. Paperback, 1997. pp. 332-52.

[5]Jane Greenfield. ABC of bookbinding; a unique glossary with over 700 illustrations for collectors and librarians. New Castle, Carlton, 2002.

[6] Barrett, Timothy. Japanese Papermaking: Traditions, Tools, and Techniques. Colorado: Weatherhill, 1992; Bidwell, John. Fine Papers at the Oxford University Press. Whittington: Whittington Press, 1999.

[7] “Marian Bantjes: Intricate Beauty by Design.” Ted Talks. 2010.

[8] Kelly, Rob Roy. American Wood Type 1828 – 1900: Notes on the Evolution of Decorated and Large Types and Comments on Related Trades of the Period. New York: Da Capo Press, 1977; Staff, Frank. The Picture Postcard & Its Origins. New York: F.A. Praeger, 1966.

[9] “Palaeography, 1500-1800: A Practical Online Tutorial.” The National Archives. 2006.

[10] Wieck, Roger S. Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art. New York: George Braziller, 1999.

[11] Needham, Paul. Twelve Centuries of Bookbindings, 400-1600. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1979.

[12] Lock, Margaret. Bookbinding Materials and Techniques, 1700-1920. Toronto: Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild, 2003.

[13] Hanmer, Karen. Biblio Tech: Reverse engineering historical and modern binding structures. 2013.

[14] Golden, Alisa J. Making Handmade Books: 100 Bindings, Structures & Forms. New York: Lark Crafts, 2010.

[15] Drucker, Johanna. The Century of Artists’ Books. 2nd ed. New York: Granary Books, 2004.

[16] De Heer, Esmée. “The Abominable Digital Artists’ Book: Myth or Reality?” Universitiet Leiden: Masters Theses. 20 November 2012.

[17] “Transforming Artist Books.” Tate. August 2012.

[18] “About.” Non-Visible & Intangible. November 12, 2012.

Bibliography

“About.” Non-Visible & Intangible. November 12, 2012.

“About Pinterest.” Pinterest. 2015.

“Advance Reading Lists.” Rare Book School. 2015.

Barrett, Timothy. Japanese Papermaking: Traditions, Tools, and Techniques. Colorado: Weatherhill, 1992.

Bidwell, John. Fine Papers at the Oxford University Press. Whittington: Whittington Press, 1999.

“Curriculum | Book Arts.” Book Art @ Alamaba. University of Alabama. 2015

de Heer, Esmée. “The Abominable Digital Artists’ Book: Myth or Reality?” Universitiet Leiden: Masters Theses. November 20, 2012.

Drucker, Johanna. The Century of Artists’ Books. 2nd ed. New York: Granary Books, 2004.

Golden, Alisa J. Making Handmade Books: 100 Bindings, Structures & Forms. New York: Lark Crafts, 2010.

Grab, Elizabeth. “Book Artists’ Core Collection.” Pinterest. December, 2015.

Hanmer, Karen. Biblio Tech: Reverse engineering historical and modern binding structures. 2013.

Kelly, Rob Roy. American Wood Type 1828 – 1900: Notes on the Evolution of Decorated and Large Types and Comments on Related Trades of the Period. New York: Da Capo Press, 1977.

“List of Courses.” Center for the Book. University of Iowa. 2015.

Lock, Margaret. Bookbinding Materials and Techniques, 1700-1920. Toronto: Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild, 2003.

“Marian Bantjes: Intricate Beauty by Design.” Ted Talks. 2010.

Needham, Paul. Twelve Centuries of Bookbindings, 400-1600. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1979.

“Palaeography, 1500-1800: A Practical Online Tutorial.” The National Archives. 2006.

“Press.” About Pinterest. 2015.

Staff, Frank. The Picture Postcard & Its Origins. New York: F.A. Praeger, 1966.

“Transforming Artist Books.” Tate. August 1, 2012.

Wieck, Roger S. Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art. New York: George Braziller, 1999.

[Originally posted on Rambling Rambler Press @ WordPress on 9 December 2015]

]]>The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian: A Defense

Introduction

Books, particularly those written for young adults, are challenged regularly and banned with frequency in the United States. According to the American Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom and Public Information Offices “up to 85% of book challenges receive no media attention and remain unreported.”[1] 2014 saw 311 challenges reported. If we include the estimated 85% of unreported challenges, the number increases to roughly 575 books challenged in one year. Of the 311 reported challenges, 80% of them included ‘diverse’ material.[2] The Intellectual Freedom and Public Information Offices define ‘diverse’ according to Malinda Lo: “non-white main and/or secondary characters; LGBT main and/or secondary characters; disabled main and/or secondary characters; issues about race or racism; LGBT issues; issues about religion, which encompass in this situation the Holocaust and terrorism; issues about disability and/or mental illness; non-Western settings, in which the West is North America and Europe.”[3]

With all of these statistics in mind, it’s no wonder that Sherman Alexie’s young adult novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, published in 2007, tops the 2014 list of the ten most challenged books. The main character, Junior, self-identifies as a poor, lisping, stuttering, physically- and socially-awkward, Native American brown kid that lives on a reservation and gets beat up regularly, with brain damage, seizures, alcoholic parents and a shut-in sister.[4] Because of how Junior navigates all of these challenges and more, this story represents one of the most important young adult books produced in the past decade. It is our duty—firstly as citizens and secondly as librarians—to defend young adult books with diverse characters like Alexie’s main character from well-meaning, misinformed censors.

The Complaints

According to the ALA’s website, the primary objections brought against The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian include “anti-family, cultural insensitivity, drugs/alcohol/smoking, gambling, offensive language, sex education, sexually explicit, unsuited for age group, and violence” with “depictions of bullying” thrown in for good measure. Sherman Alexie, in his Wall Street Journal response to naysayers, adds depravity, “domestic violence, drug abuse, racism, poverty, sexuality, and murder,” to the list of ‘objectionable material’.[5] Not only does Junior encompass nearly every aspect of diversity, he also experiences nearly every aspect of subject matter thought inappropriate for young adults.[6]

At Antioch High School, in a suburb of Chicago, for example, seven parents came before the school board requesting Alexie’s book be removed from the summer reading list, the curriculum, and the library unless accompanied by a warning label “because it uses foul, racist language and describes sexual acts.”[7] Mother Jennifer Andersen read the book to help her son understand it and proceeded to cross out passage after passage that she felt was inappropriate for any high school freshman.[8] She also commented that while she knows that kids curse, if books with profanity are included in the curriculum, “the students will believe the school condones it.”[9]

Why the Censors Are Just Plain Wrong

Before breaking down why the objections to The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian represent the very same reasons why it should be required reading for every middle- and high-schooler, it behooves my argument to include the many accolades awarded to Alexie’s book by widely recognized and respected authorities on literature:

- National Book Award Winner for Young People’s Literature

- New York Times Notable Book of the Year for Children’s Books

- Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year

- A NAPPA Gold Book

- School Library Journal Best Book of the Year

- An Amazon.com Best Book of the Year

- Kirkus Reviews Best YA Book of the Year

- A BBYA Top Ten Book for Teens

- NYPL Books for the Teen Age

- PW “Off the Cuff” Favorite YA Novel

- A Boston Globe Horn Book Winner

- Odyssey Award for Best Audio Book

The awards specifically for teens and young adult books are bolded, representing eight out of the twelve, more than half the list. I am not alone in seeing this book as required reading for adults and young adults alike. With the backing of highly authoritative voices, I can now continue to refute each objection as unfounded.

Anti-family is the simplest issue to address. I can only assume that censors are pointing to the alcoholism of Junior’s parents and the realistic tension that exists between a teenager and his family. But consistently throughout the book, we see Junior’s understanding of both how his family became what it is and of the history behind each member’s actions. Junior’s parents are trying their best and Junior accepts them with love as they both support and disappoint him. For example, when the family dog becomes terminally ill and requires prohibitively expensive veterinary care, his parents euthanize the dog, despite their son’s desperate objections. Even while Junior is deeply upset, he couches the story in his family’s reality; they can’t even afford to have food in the house on a daily basis, let alone pay exorbitant vet bills for a dog that’s dying anyways. He says:

I was hot mad. Volcano mad. Tsunami mad.

Dad just looked down at me with the saddest look in his eyes. He was crying. He looked weak.

I wanted to hate him for his weakness.

I wanted to hate Dad and Mom for our poverty.

I wanted to blame them for my sick dog and for all the other sicknesses in the world.

But I can’t blame my parents for our poverty because my mother and father are the twin suns around which I orbit and my world EXPLODE without them. [10]

Junior readily admits that his whole life is dependent upon loving his family, even while he wants to hate them. This is one of the most widely exhibited struggles for teenagers in the U.S. How can Junior’s constructive, positive understanding of this struggle be construed as anti-family?

The second criticism of the book is its “cultural insensitivity,” AKA racism. Jimmie Durham, a Cherokee artist, wrote an essay called “A Central Margin” addressing the myth at the core of the American identity of the “absent/absented ‘Indian’ body.”[11] Essentially, the life of a Native American in the United States is one of systematic and continual “cultural insensitivity” to which many Natives respond “with that quietly outrageous Indian humor that has been so valuable to our survival.”[12] By suppressing the cultural criticism and display of race relations displayed in The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, censors continue this obliteration of Native voices in the U.S. Without a marginal voice speaking up and pointing out racist societal constructs, many people of the dominant culture remain blind to the flaws in the system that oppress others.[13] Aside from this highly problematic issue of suppressing stories depicting the realities of living in a system of racism, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian is the first and likely only exposure to Native Americans—presented on their own terms—that a majority of adults and young adults will ever encounter. A dearth of Native voices exists in pop cultural depictions of Native Americans, which is a major part of what hinders the U.S. from collectively coming to terms with the colonial racism at the core of our creation and identity. Authors like Sherman Alexie should be circulated more widely for their marginalized perspective and social criticism, not less.

The third grouping of objections can be categorized generally into Sin and Depravity, in this case: substance abuse, gambling, offensive language, the expression of sexuality and domestic violence. As Alexie himself points out in his Wall Street Journal response referenced earlier, the movement to ‘protect’ children from these subject matters is highly privileged and comes far too late. He posits that not only are cultural critics too late to protect an overwhelming majority of both ‘at-risk’ and mainstream kids, they aren’t actually interested in protecting black American teens “forced to walk through metal detectors” to go to class, or Mexican American teens from “the culturally schizophrenic life of being American citizens and the children of illegal immigrants,” or “poor white kids trying to survive the meth-hazed trailer parks,” or teen mothers and fathers from sexually explicit material, or “victims from rapists.” Instead, these censors wish to protect their limited “notions of what literature is and should be.”[14] But this interferes with the purpose of reading for so many young adults. YA books are most important when they provide a mirror for readers to see themselves and their experience in the story. That sensation of solidarity and having a safe space to see how others in their situation manage can be an essential coping mechanism. Junior’s story is particularly important in this process because he recognizes and faces all of his challenges, filling the book with “positive life-affirming messages and has an especially strong anti-alcohol message.”[15] Since ‘objectionable materials’ are a daily part of lives for kids of all ages and socio-economic levels, Junior’s navigation through these issues acts as a bolster. Alexie poignantly says this of the value of reading books that realistically reflect the lived experience of young adults:

[T]here are millions of teens who read because they are sad and lonely and enraged. They read because they live in an often-terrible world. They read because they believe, despite the callow protestations of certain adults, that books-especially the dark and dangerous ones-will save them… I read books about monsters and monstrous things, often written with monstrous language, because they taught me how to battle the real monsters in my life… And now I write books for teenagers because I vividly remember what it felt like to be a teen facing everyday and epic dangers. I don’t write to protect them. It’s far too late for that. I write to give them weapons–in the form of words and ideas-that will help them fight their monsters. I write in blood because I remember what it felt like to bleed. [16]

Kids absorb their environments and need a place to process those experiences. Just because those environments are ‘objectionable’ doesn’t justify the whitewashing of them. Even for kids who aren’t exposed to troubles like poverty, domestic violence and substance abuse, books like The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian act as a window of understanding into the various experiences of those around them, allowing all of us to be more aware of and sensitive to one another. The problems associated with censoring this book are far more troubling than any of the complaints made to justifying its banning.

[1] “Statistics,” Banned & Challenged Books, American Library Association.

[2] That 80% containing diverse material roughly equals 250 of the 311 books. “2014 Books Challenges Infographic,” Banned & Challenged Books, American Library Association.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Sherman Alexie, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2009), 1-6.

[5] Sherman Alexie, “Why the Best Kids Books Are Written in Blood,” Speakeasy,Wall Street Journal, 9 June 2011.

[6] With the prevalence of ‘diverse’ books comprising the bulk of challenges, one has to wonder if diversity doesn’t automatically mean objectionable for those inclined to instigate censorship. The ALA’s Kristin Pekoll also brings up this troubling point in her comments in MPR News’ coverage of Banned Book Week; Tracy Mumford, “Banned Books Week: Celebrating the Controversial,” MPR News, 29 September 2015.

[7] Ruth Fuller, “Some Parents Seek to Ban ‘The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,’” Chicago Tribune, 22 June 2009.

[8] Ibid.

[9] In refutation to Andersen’s concern, John Whitehurst, chairman of the English department, sites the parallel example of teen suicide in Romeo and Juliet. “Kids know the difference” between a book and school policy; Ruth Fuller, “Some Parents Seek to Ban ‘The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,’” Chicago Tribune, 22 June 2009.

[10] Sherman Alexie, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2009), 11.

[11] Jimmie Durham. “A Central Margin,” in The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s (New York: Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, 1990), 164.

[12] Ibid, 172.

[13] For further examples of this, see James Luna The Artifact Piece, installation/performance, Museum of Man, San Diego, 1986; “The Redskins’ Name – Catching Racism,” Comedy Central, 25 September 2014; and Ricardo Caté, Without Reservations (Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith, 2012).

[14] Sherman Alexie, “Why the Best Kids Books Are Written in Blood,” Speakeasy, Wall Street Journal, 9 June 2011.

[15] Ruth Fuller, “Some Parents Seek to Ban ‘The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,’” Chicago Tribune, 22 June 2009.

[16] Sherman Alexie, “Why the Best Kids Books Are Written in Blood,” Wall Street Journal.

Bibliography

“2014 Books Challenges Infographic.” Banned & Challenged Books. American Library Association.

Alexie, Sherman. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. New York: Little, Brown & Co. 2009.

Alexie, Sherman. “Why the Best Kids Books Are Written in Blood.” Speakeasy.Wall Street Journal. 9 June 2011.

Durham, Jimmie. “A Central Margin.” in The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s. New York: Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, 1990: 162-179.

Fuller, Ruth. “Some Parents Seek to Ban ‘The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.'” Chicago Tribune. 22 June 2009.

Mumford, Tracy. “Banned Books Week: Celebrating the Controversial.” MPR News. 29 September 2015.

“Statistics,” Banned & Challenged Books. American Library Association.

“The Redskins’ Name – Catching Racism.” Comedy Central. 25 September 2014.

[Originally posted on Rambling Rambler Press @ WordPress on 14 October 2015]

]]>