For UNC Art Department professor Dorothy Verkerk’s Fall 2016 course Early Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts, Professor Verkerk requested that each student select a pre-1100 manuscript of any region upon which to focus. Compelled by the portability and intimate style of the Irish pocket gospels, I chose to investigate how readers of the time might have interacted with and understood the Irish pocket gospels.

What follows is the result of that investigation.

Introduction

Scholarship on the medieval period of what is now Western Europe and the United Kingdom displays a distinct preference for the mid- to late- portion of the period, neglecting history prior to 1100. This is perhaps due to the pre-1100’s comparative lack of clear archaeological and material evidence. Perhaps it is due to the period’s isolation from the Renaissance, the darling of academic imagination and the foundation for our current culture. I posit, however, that the period’s neglect is likely due the modern mind’s inability to fully adopt a “period eye” for pre-literate, temporally distant cultures like those of the early medieval period.[1] Even the way the previous sentence frames the pre-1100s as ‘pre-literate’ privileges a post-Renaissance perspective that resists acknowledging the earlier time on its own terms, preferring instead to understand it in relation to our assumption that literacy is the natural and inevitable path an oral culture must take to be sophisticated. As art theorist Michael Baxandall writes in his essay on the period eye,

one brings to the picture [or any historical materials] a mass of information and assumptions drawn from general experience. Our own culture is close enough to the Quattrocento for us to take a lot of the same things for granted and not have a strong sense of misunderstanding the pictures; we are closer to the Quattrocento mind than to the Byzantine [or early medieval], for instance. This can make it difficult to realize how much our comprehension depends on what we bring to the picture.[2]

But, as historian Brian Stock investigates in his research on the impact of literacy on oral cultures, literacy fundamentally changes the way we understand ourselves, our relationships, and construct and interact within societies.[3] We, as literate people in a literate culture, must set aside the basis of our entire worldview to glimpse the way one in an oral culture might understand reality.

Ireland—the setting of my investigation—was an entirely oral culture until the introduction of Christianity in the early 400s C.E[4] Even with the rapid adoption of Christianity and a growing trust in the written word (upon which the Catholic Church depended for its authority), Ireland remained predominantly oral and illiterate deep into the medieval period, with only a sliver of the upper and the clerical classes boasting full literacy.[5] As such, the texts of early medieval Ireland from 600-900 C.E were primarily Christian, and the Irish scribes developed a distinctly Irish form of religious text in pocket gospels.[6] These gospel books were small, as their name suggests, diminutive in size and weight in order to accommodate a more “intimate, almost private” style of reading and to fit within the tooled and locked leather satchels, called cumdachs, that their monks wore around the neck (fig. 1).[7] Though some of these pocket gospels received additional liturgical passages and accompanying materials later, the standard pocket gospels of the 7th-10th centuries contained only the four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.[8]

Textuality in the early medieval period

Literacy goes far beyond the ability to read words and a preference for written words over aural authority.[9] In the medieval period, literacy existed within a spectrum from complete literacy to complete illiteracy, with most of those outside of complete illiteracy operating within partial literacies. When an oral culture like Ireland’s begins to incorporate the written word into its traditions, the culture is not defined by literacy or illiteracy, but by the “variety and abundance” of collaborations between the two, resulting in what Stock calls a textual culture.[10] Textuality is a more appropriately term than literacy for the early medieval Irish relationship with the written word, since it doesn’t divorce the written word from oral culture’s preference for speaking and hearing. [11] The early introduction of the written word into an oral culture results in a focus on the use of and interaction with text in certain very specific settings, not the ability to read and comprehend written ideas.[12] Instead, the book and paper take on a role in which they are representational containers of authority that serve as objects of use and facilitators of certain experiences. They do not function as texts to be read for direct textual understanding. Or, as Stock puts it, textuality focuses “not [on] what texts are, but what people do with them.”[13] For instance, the presence of a leaf of vellum at the time of an oral land transaction was sufficient to lend the agreement permanent legal authority.[14]

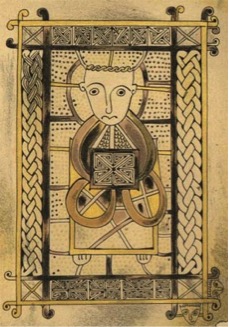

Due to the highly oral nature of the textual culture of early medieval Ireland, it is virtually guaranteed that the owners of these pocket gospels would have had the books’ contents memorized, marking the script and illumination as visual queues rather than as decorated words to be read line by line. David B. Morris adds to this supposition in his essay “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” noting that medieval church readers would have practiced repetition and purposeful memorization to make the gospels familiar and accessible for reflection, even when the text was not legible before them.[15] This is reinforced again by the continued relationship with textuality even two centuries after pocket gospels fell out of fashion; despite the significant move towards a more literate culture by this time, prayer books in the form of books of hours (fig. 2) used image and text as “memory guides for the reader…[that] operated as effective and appropriate cues for contemplation during the recitation of the familiar prayers.”[16] The function of memory in a textual-oral culture still held with the growth of literate culture.

Use of the book as an object

As mentioned previously, the containers for words—both leaves of parchment and books—held power in early medieval Ireland. This power was twofold. Firstly, they acted as a means for the Church to harness non-Christian magical practices and thinking; secondly and relatedly, they acted as objects that gave protection and, thus, deserved protection.

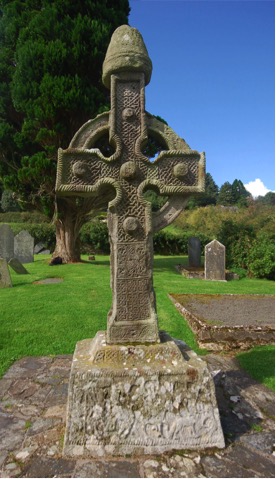

The book acted as a means of translating the Irish magic of power and miracle through the elision of local magical iconography and symbolic functioning, which was part of a larger movement of appropriation sanctioned by Pope Saint Gregory I, holder of the papal seat from 590 to 604 C.E[17] As Valerie I. J. Flint points out in her book The Rise of Magic In Early Medieval Europe, officials nurturing the introduction of Christianity into Ireland regularly borrowed and adapted non-Christian sites, objects and emotional associations with Christian ones, using everything from the placement of Christian sites to iconography on freestanding crosses to accomplish the “peaceful penetration of societies very different from their own.”[18] Like all good salespeople, the clergy framed Christianity as the newest and most effective form of magic to accomplish what the people were already seeking in their non-Christian practices. As the power of the Christian Church lies in its canonical scripture, it follows that it would have a vested interest in impregnating the Bible and other Christian texts with mystical power. Reverence for the power of books would be a natural progression in a textual culture that developed out of a religious context. With books holding the divine magic of the word of God, it follows that books themselves would be revered as magical objects, and the clergy would themselves be honored as those who could provide access to and dispense this power.

In order to further the effort to align Christian texts with non-Christian mysticism, illuminators and those executing other Christian crafts used the local aesthetic vocabulary. Flint notes that

[a]s impressive memories of non-Christian hanging sacrifices, special stones and woods, omens, and supernatural means of healing are carried vividly and carefully into the monuments[, ivories, metalwork, and illuminated manuscripts] proclaiming Christianized and supernatural power at the new shrines then, so too, on a rather smaller scale, are echoes of other forms of supernatural practice, such as amuletic rings and knots, weaving, and binding. All of these, obviously, are to be rendered subordinate to the new ways of invoking the supernatural; yet also they are still to form part of it, where this is possible.[19]

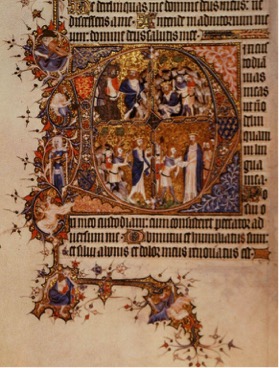

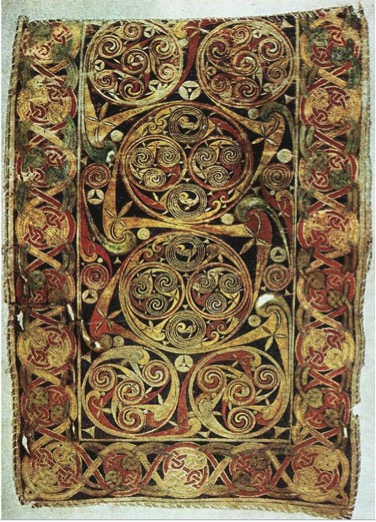

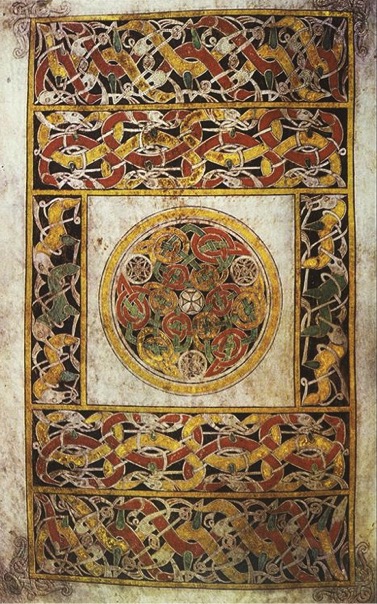

Thus, it is unsurprising that the monkish illuminators would have used the mesmerizing iconography known to the Irish people. The Book of Durrow’s carpet pages (figs. 3 and 4), some of the most famous pages from any of the pocket gospels, provide the perfect opportunity to observe the direct parallels drawn between both carving and metalworking and illumination. Observe how the interlacing, abstracted animals and triskeles in the Book of Durrow pages, the north high cross at Ahenny (figs. 5 and 6) and the Tara brooch (figs. 7 and 8) match so closely. They are drawn directly from the pre-existing Insular art so recognizable to and standardized by the people of Ireland. This iconography would have been associated with status and protection.[20]

The book provided protection and was something that needed protecting. Since the Church had effectively used the attitude of a textual culture towards books to its advantage, the people associated them with magic and all of its associated power. The protective quality lent to these pocket gospels was so enduring that even into the 17th century, the Irish public still viewed them as powerful protective objects; a farmer went so far as to immerse a section in his cattle’s drinking water to cure them of illness.[21] Within the medieval period, these pocket gospels were seen as so protective that clans used them in battle as a talisman—known as a cathach or battle book—for victory.[22] One cathach in particular boasts an infamous history. The Cathach of St. Columba—also known as Colm Cille—was used in battle by the Donegal clan until the 11th century (fig. 9).[23] In fact, the sanctity of texts was regarded so highly that this book inspired a battle of its own prior to the clan’s ownership. St. Finnian lent the book to Colm Cille, who created an unauthorized copy of the text, which Colm Cille refused to give back to St. Finnian. A failed arbitration between the parties led to the battle of Cul Dremhne in 561 C.E.[24]

These pocket gospels required protection of their own in turn, in order to preserve the positive magic of God from the influence of evil.[25] Externally, the books were guarded by cumdachs. These satchels—or sometimes altars—had locks to protect from theft, as is evident from one of the only extant medieval satchels (fig. 10), which held the Book of Armagh. The satchel also exhibits the iconography already seen in the north high cross at Ahenny and the carpet pages from the Book of Durrow. The interlacing that brings to mind wattle fencing is likely the most associated with protection and containment. This type of hurdle was used to contain livestock and to demarcate land ownership or purposes, so it follows that it was also meant to serve as a containment or binding of the divine word to the pages of the book and to act as a deterrent to evil forces that might enter and corrupt it.[26] These weavings only bound the exterior flap of the satchel, but also portions of the Tara brooch (fig. 8) and the internal illuminations in many of the pocket gospels (fig. 1, 3 and 4).

Use of the book as a facilitator of experience

The book, as is suggested by the protective ornament, served as the incarnation of and access to the Christianized magic of the divine. Eleventh through twelfth century scholar and clergyman Hugh St. Victor cements this idea in his codification of principles around reading—developing prior to and during his time—when he writes,

The divine Wisdom, which the Father has uttered out of his heart, invisible in Itself, is recognized through creatures and in them. From this is most surely gathered how profound is the understanding to be sought in the Sacred Writings, in which we come through the word to a concept, through the concept to a thing, through the thing to its idea, and through its idea arrive at Truth.[27]

It is this divine truth manifested within and made accessible through Christian texts that held the purpose behind reading for early medieval monks in Ireland. Reading allowed clergy to seek, and potentially find, the supreme truth they sought through a prescribed process frequently referred to as the Lectio Divina and referred to in Hugh’s text on reading as the ‘four steps’ (which were, in fact, numbering five).[28] Hugh’s version of the Lection Divina follows this order: (1) study or reading for understanding; (2) meditation for counsel; (3) prayer to make petition; (4) performance, which is the process of seeking the truth; and, finally and nearly impossible to achieve, (5) contemplation upon the previous four steps for the finding of truth. The steps were theoretically succeeding, but required frequent regression to earlier steps to begin the process over in order to better achieve the step of finding divine truth.[29]

This process termed ‘reading’ has very little to do with reading as we now understand it, however. It was not a literal reading of the words on the page; instead, early medieval ‘reading’ represented a full-body reflective process embedded in the oral culture’s mentality that “you know what you can recall.”[30] This attitude results in religious books for a textual culture, books serving as a “written series of things readied for oral recall” to achieve intellectual and spiritual improvement.[31] It is also this attitude of textual culture that implies that the pages of the pocket gospels would likely have served more as cues for familiar, oft-visited memory paths than lines literally reread repeatedly.[32] The memory-focused approach allowed each recitation to follow the path of the Lectio Divina—a reader was not caught up in the process of reading, but in the process of reflection on the words being ‘read.’[33]

The idea of the book as a tools rather than as reading material actually fits comfortably within the progression of Western, Mediterranean-oriented culture both before and after the early medieval period. In the Roman tradition—as described by archaeologist Bettina Bergmann—memory training involved building an argument or recitation by building a mental home in which one travelled linearly past paintings depicting the argument as it proceeded.[34] Gospel books, thus, act as a physical manifestation of this guide in the early medieval period, whose Christian education long drew from Classical education and traditions.[35] The late medieval and early Renaissance periods also show a continuation of this progression in the form of books of hours, mentioned previously. These prayer books served to bring the reader closer to the truth contained within God’s word through the same meditative process seen in the Lectio Divina of the early medieval period, though for laypeople rather than for clergy.[36]

The experience facilitated by memorization and ‘reading’ in the Lectio Divina approach—as argued by both Hugh St. Victor and David B. Morris—promises not just spiritual health, but also bodily health.[37] During the early medieval period, a distinction was not drawn between the two; thus, to cure one’s spiritual ailments through the Lectio Divina process of accessing God’s healing truth, one also cures bodily ailments, thought to be manifestations of spiritual evil or weakness.[38] Hugh best phrases the dual benefits of Lectio Divina and the meditation encompassed within it when he writes,

[t]he start of learning, thus, lies in reading, but its consummation lies in meditation; which if any man will learn to love it very intimately and will despite to be engaged very upon it, renders his life pleasant indeed, and provides the greatest consolation to him in his trials. This especially it is which takes the soul away from the noise of earthly business and makes it have even in this life a kind of foretaste of the sweetness of the eternal quiet.[39]

Meditation removes the reader from the weaknesses of the body to return it to the perfection of God’s original creation. Once the reader returns to the material word after basking in the light of God’s truth, he is meant to return to his body, healed.

Conclusion

The book, in the form of pocket gospels in early medieval textual Ireland, served as an object of protection and as a means of accessing divinely blessed states of wellbeing. It is the culture of early medieval Ireland that allowed these functions to develop, thanks to the still fluctuating cultural relationship with literacy and non-Christian magic. Christian texts gained their power because they became bridges, a bridge between the Christian and non-Christian; a bridge between the oral and literate culture; and a bridge between divine power and humankind.

Figures

Bibliography

Bäuml, Franz H. “Varieties and Consequences of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy.” Speculum 55.2 (1980): 237-265.

Baxandall, Michael. “The Period Eye.” Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988.

Bergmann, Bettina. “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii.” The Art Bulletin 76.2 (1994): 225-256.

“Book of Durrow.” Pangur’s Bookshelf. 24 Aug. 2014.

“Cathach of St. Columba.” Encyclopedia of Irish and Celtic Art.

Cunningham, Lawrence S. and Keith J. Egan. Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition. New York: Paulist Press, 1996.

Cusack, Margaret Anne. “Mission of St. Palladius.” An Illustrated History of Ireland.

Flint, Valerie I. J. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991.

Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

“Hurdles & Fencing.” The Dorset Woodsman. 2016.

McGurk, Patrick. “Irish Pocket Gospel Book.” Sacris Erudiri 8 (1956): 249-269.

Morris, David B. “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 (Summer 2006): 539-561.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Stock, Brian. After Augustine: The Meditative Reader and The Text. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Stock, Brian. The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983.

Stock, Brian. Listening for The Text: On The Uses of The Past. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

Stocks, Bronwyn. “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours.” Word & Image 32.1 (2007): 16-24.

“The Cathach / The Psalter of St Columba.” Royal Irish Academy. 12 Sept. 2016.

Westwell, Chanry. “Put It In Your Pocket.” Medieval Manuscripts Blog. December 18, 2013.

Wiener, James. “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art.” Ancient History Et Cetera. 30 Oct. 2014.

Yvard, Catherine. “Pocket Books.” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[1] The period eye is a tool for scholars to construct—using contemporary documentation and evidence—the context and cultural signifiers of a time, enabling a fuller acknowledgement of and negotiating around modern biases and assumptions; Michael Baxandall, “The Period Eye,” Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988), 29-108.

[2] Baxandall, “The Period Eye,” 35.

[3] Stock investigates this idea throughout three of his books; Brian Stock, Listening for the Text: On The Uses of The Past (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990); Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983); and Brian Stock, After Augustine: The Meditative Reader and The Text, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

[4] In 431 C.E., Pope Celestine commissioned Palladius to mister to the Irish believing in Christ, suggesting that Christianity had established itself sufficiently to garner attention from the clergy in the decades before 430 C.E.; Margaret Anne Cusack, “Mission of St. Palladius,” An Illustrated History of Ireland.

[5] Stock, Listening for the Text, 142; Franz H. Bäuml, “Varieties and Consequences of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy,” Speculum 55.2 1980: 238.

[6] While the pocket gospel tradition remains strong through the early 12th century, I chose the period from 600-900 C.E. because the 600s marks the earliest known examples of this type of book and the 900s starts the period in which scribes began inserting additions and developing a more Anglo-Saxon style of illumination; Chanry Westwell, “Put It In Your Pocket,” Medieval Manuscripts Blog, December 18, 2013; Catherine Yvard, “Pocket Books,” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[7] Patrick McGurk, “The Irish Pocket Gospel Book,” Sacris Erudiri 8 1956: 250.

[8] Catherine Yvard, “Pocket Books,” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[9] Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World (New York: Routledge, 2002), 5-6.

[10] Stock, Implications of Literacy, 42.

[11] Ibid., 145.

[12] Ibid., 143-144.

[13] Ibid., 144.

[14] Ibid., 144.

[15] David B. Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 2006: 551.

[16] Bronwyn Stocks, “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours,” Word & Image 32.1 2007: 16.

[17] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 256.

[18] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 4 and 254-257.

[19] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 260-261.

[20] James Wiener, “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art,” Ancient History Et Cetera, 30 Oct. 2014.

[21] “Book of Durrow,” Pangur’s Bookshelf, 24 Aug. 2014.

[22] “Cathach of St. Columba,” Encyclopedia of Irish and Celtic Art.

[23] “The Cathach / The Psalter of St Columba,” Royal Irish Academy, 12 Sept. 2016.

[24] Ibid.

[25] James Wiener, “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art,” Ancient History Et Cetera, 30 Oct. 2014.

[26] “Hurdles & Fencing,” The Dorset Woodsman, 2016.

[27] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, trans. Jerome Taylor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 122.

[28] Originating in the writings of Saint Benedict in the 6th century, Lectio Divina traditionally proceeded through a fourfold process: (1) reading; (2) meditation; (3) prayer; and (4) contemplation. Lawrence S. Cunningham and Keith J. Egan, Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition (New York: Paulist Press, 1996), 38.

[29] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, 132-133.

[30] Ibid., 93-94; David B. Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 2006: 542; Ong, Orality and Literacy, 3.

[31] Ong, Orality and Literacy, 121.

[32] Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” 551.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Bettina Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii.” The Art Bulletin 76.2 1994: 225.

[35] Stock, Implication of Literacy, 16.

[36] Stocks, “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours”: 16.

[37] Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” 551.

[38] Ibid., 551-552.

[39] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, 92-93.

N.B. All images reproduced under the principle of Fair Use.