For UNC Department of Classics professor Hérica Valladares’ Fall 2016 course on Roman Architecture, I decided to focus on how the type of model researchers choose to represent and recreate Roman Villas influence the conclusions they’re capable of or likely to find. What follows is the result of that investigation.

Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.

— George Box and Norman Draper, Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces, 1987

Introduction

Statistician George Box was a man with a conditional love of models. He maintained that, while simple models can approximate reality, no model could entirely represent the real world exactly. Despite this inability, Box did allow that a model could “supply a useful approximation to reality,” rendering it a handy tool.[1] It is with this wary consideration in mind that I investigate how modeling methods influence our understanding of Roman villas.

Architectural models are useful tools in that they enable scholars to better understand their research subject and allow members of the public to better engage with their cultural history. As Mount Holyoke professor Michael T. Davis shared in his presentation at Duke University’s 2016 digital humanities symposium, “we, as a species, tend towards a stubborn positivism, demanding sensory and—I think, above all—visual confirmation as the means by which we, in the words of Thomas Aquinas, “gather the intelligible truths of all things.”’[2] Interacting with a visual model can bring history to life for schoolchildren, inspiring greater investment in local communities, in a school subject or in a career path. For historians, building a visual model can test literary and archaeological evidence against the realities of gravity, humidity, time of day or year, and sight lines, among other physical restrictions to reconstruct what was probable in the construction or arrangement of a building.

From 19th and 20th century to present day rediscoveries sites, Roman buildings have proved a rich area for modeling projects. Since they typically survive as limited remains or as wonders that dominant scholarship decided should concern the world at large, researchers required a means of compiling their observations into a cohesive and observable form for their peers, resulting in that sensory, visual confirmation of a model, as Davis mentioned.[3] Sites such as Pompeii have proved especially fruitful, given the relative volume of preserved evidence unmediated by further societal interventions until its mid-eighteenth century rediscovery, enshrining the site in the collective archaeological imagination. But locations with fewer intact architectural and material remains, such as the United Kingdom, have also inspired interest in reconstruction. When first approaching this paper, I planned to direct my geographic focus to models of Romano-British villas, since Britain maintains such visible enthusiasm for reliving its glorious history.[4] However, between limited interest in digital reconstruction of these numerous villa sites, the departure of the provincial architecture from its Italian counterparts, and the democratic audience targeted by Britain’s physical modeling projects, such a scope proved too limiting. Consequently, this study includes models of villas from both Pompeii and from Britannia.

Villas are particularly interesting sites to reconstruct, since Roman home structures tended to be locations that fluidly melded the public and private spheres as we now understand them. For instance, villas of Britannia were often part of a larger farming estate that would adjoin granaries and also acted as the place where the dominus would conduct business and shelter the household.[5] Pompeian villas operated similarly, with fluidity between public business and private domesticity.[6] Until recently, scholars set out to uncover the fixed purpose of a room, but with the holistic incorporation of anthropology, archaeology and social art history into both written scholarship and models, that pattern has shifted towards a greater emphasis on letting the evidence on the ground speak for itself, encouraging scholars to draw conclusions from the evidence rather than theory.[7] Reconstruction models help scholars experience the evidence sensorially to uncover the otherwise unforeseen in the most likely mundane realities of life within these villas. Investigating villas provides human connection not just for scholarship, but also for average citizens, as well, allowing them to envision themselves in these histories so to bridge the relevancies of the past and the present.

History of models as a means of reconstruction

Before digging into the villa models specifically, however, I first wish to progress quickly through the evolution of archaeological architectural models and how the conversation around models has remained relatively static, despite the extended time frame and shifting media. As Stefano de Caro recounts in his introduction to the 2002 book Houses and Monuments of Pompeii: The works of Fausto and Felice Niccolini, “[a]t the very moment that creating a “virtual” Pompeii in the interest of conserving the ancient city has been put forward, here is an opportunity to present Le case ed i monumenti [(originally published 1854)], which in its own way was the first virtual Pompeii.”[8] Clearly the discussion around models persists unabated.

With the early-nineteenth century growth of archaeology as a discipline and an increasing cultural concern with the scientific, models became a pressing preoccupation. As Roberto Cassanelli describes in his essay on “Images of Pompeii: From Engraving to Photography,” the early forms those models took included both traditional modes of representation—sketches, watercolors, gouache paintings, lithographs and engravings, and ground plans—as well as developing technologies—photography in the form of daguerreotype and collotypes.[9] While not models in the sense of allowing the viewer to sensuously interact with and imagine the space, these two-dimensional renderings opened the discussion ongoing in modeling projects to present day, specifically the debates over whether a model is a greater reflection of the perspectives of the modern culture than the realities of the ancient evidence and whether a model is more dangerous than useful, as it can take on a life of its own by creating a sense of certainty that disregards the nuances of historical evidence and educated conjecture.

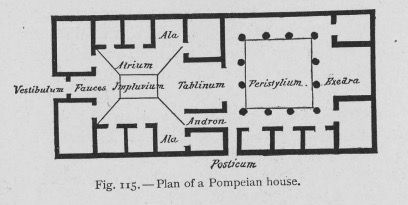

August’s Mau’s model of the ideal Pompeian home from his book Pompeii: Its Life and Art captures both issues beautifully. He begins the chapter on Pompeian houses by acknowledging how source material on domestic architecture in Italy is limited to Vitruvius’ treatise De architectura and the remains of Pompeii itself. He goes on to provide his conclusion that, despite “many variations from the plan described by the Roman architect [Vitruvius]”—Pompeian houses should still be understood to be in accordance with the treatise’s particulars.[10] After proving his general findings on the houses of the city, he supplies the reader with this ground plan model for the Pompeian house (fig. 1). This ground plan has taken on a life of its own, taught in survey courses and introductions to Pompeii across the United States with minimal intervention complicating the reading of it so as to be useful for general study, but neglects to problematize which evidences are privileged in model creation. In this case, Mau showed deference for the literary evidence rather than allowing the archaeological evidence to guide the design, which is not made clear when taking the model out of its context within the chapter, as it so often is. That preference for privileging the textual evidence also has little to do with the quality of the evidence available in Pompeii and everything to do with the way that scholarship was conducted during Mau’s time.

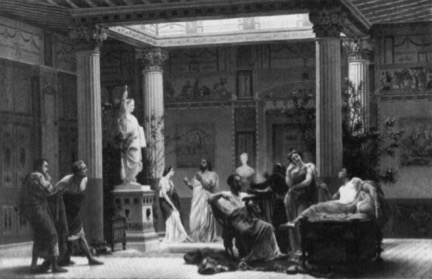

Prince Napoleon III’s Pompeian mansion reconstruction is even more reflective of the early conversations around models being more reflective of their own time than the archaeological reality. The prince’s architects modeled the palace on Pompeian villas such as that of Diomedes and the House of Pansa. The court received the reconstruction as “a rigorous restitution, … a deeply learned archaeological treatise written in stone that can be inhabited,” while also believing it “to be a symbolic expression for a modern imperial lifestyle…[that held] up a polished patrician mirror.”[11] This palatial model acted as a lens for present day concerns, not reconstruction for the sake of understanding the archaeological past. The model suited, instead, the repopulating of the Roman past with contemporary concerns and behavior, as is evident in Boulanger’s painting of a rehearsal in which the friends of the prince combine “archaeology and fiction…[by] emulate[ing] what they imagined to have been a Pompeian life of elegant leisure” (fig. 2).[12] In this case, all historical integrity is lost due to the nature of the reconstruction serving as a playhouse rather than as a true model.

The debates around how models mediate our understanding of the sites they reconstruct continue regardless of the evolution in media for reconstruction, moving through physical small-scale models, large-scale reconstructions, 3-D computer assisted drafting, visually immersive 3-D video, fully immersive 3-D gaming technology, and artificial reality.

Physical reconstructions

Model 1: physical, small-scale model of the House of the Tragic Poet

The second century BC House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii has received significant attention from archaeologists for its apparent agreement with Vitruvius’ observations in De architectura on the properly arranged and proportioned home.[13] As part of that attention, a number of models have been constructed of it. The small-scale physical model Bettina Bergmann uses in her article on “The Roman House as Memory Theater” (fig. 3-4) is particularly relevant to an investigation of how models are and are not useful in expanding knowledge of the Roman villa. She uses the model in conjunction with another computer assisted line-drawing reconstruction (fig. 5) to recontextualize the conception of the house and its decoration so that it prioritizes the likely realities of viewing and moving through the environment, as supported primarily by the archaeological record and then performed.[14]

Throughout the paper, she uses the physical reconstruction supported by the computer assisted line drawing model to draw conclusions about the strength of previous and contemporary scholars’ supposition regarding how the villa acted “as a frame for action” within the assumed social structures of private and public. Of these model-supported conclusions, she feels confident confirming the idea of the axes of private and public social differentiation based on the sight lines and wall painting indicators.[15] The model also allowed her to recontextualize the wall paintings, as they were removed from the villa and now reside in the Naples Museum in an order imposed by the institution. By drawing on the artistic rendering of the wall paintings within the rooms by archaeologists who experienced the villa after its rediscovery and before it decorative deconstruction.[16] Based on the finding of the wall painting series, Bergmann’s model undermines the traditional view of the House of the Tragic Poet as a “Homeric house,” since the order of the wall paintings does not suggest a cohesive, linear story of the Iliad being performed.[17] Instead, Bergmann suggests a new conception of the artist, one that gives them agency and credit not only their formal skills, but also their dialectic, analytical skills to create panels that were “composed in relation to each other and for th[e] space” based on repeated and responsive compositional choices that only become obvious when examined on the walls in their original order in the reconstruction and restoration enabled by the model.[18]

While Bergmann’s article provides a strong argument for the value of models as a scholarly tool in uncovering and testing theory on the Roman villa, neither argument nor model is without its flaws. The desire to repopulate the model with a figure is misleading, as the visual of a lone figure in the space leads one to believe that it might have been the wall paintings alone that directed traffic through the house, instead of other people, such as slaves. The model also misleads in the gallery-quality emptiness of the rooms. As is evident in model 1 of the digital reconstruction in the next section, having objects in the space entirely alters the way that a viewer might progress through the rooms or interact with the wall paintings, since they’re partially obscured. The model leads to the treatment of the Roman villa as a painting gallery, rather than a lived-in space.

Model 2: physical, large-scale model of the villa at Wroxeter

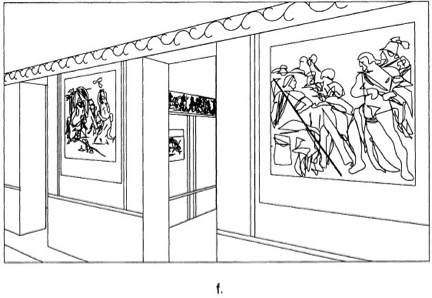

Full-scale physical models pose a different set of virtues and problems. The villa reconstruction at Wroxeter, England is one such model (fig. 6-7). The villa itself, a hybrid of the winged-corridor and courtyard villas common to Britannia (fig. 8), was located near the significant Roman settlement of Viroconium (now Wroxeter), a bustling city center and legion encampment, rediscovered in 1859. In 2010, English Heritage took on the project of reconstructing the villa to scale using ancient Roman building methods under the direction of Chester University’s professor Dai Morgan Evans. Channel 4 TV supported the effort in exchange for the building of the model to be made into a television program, “Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day.”[19] While campy and rife with reality television distractions, the program was able to convey the value in testing the literary evidence against the reality of regional environments far from Rome.

Professor Morgan Evans decided to use Vitruvius’ treatise on architecture as the primary guide for how to construct the house, despite British patterns of adapting what immigrants bring to the demands and habits of the region and the fundamental differences in architectural arrangement in the Roman atrium house and the Romano-British villa counterparts.[20] Due to this decision, as well as the lack of household objects and accompanying texts on the finalized site, the model’s value lies not in its final state or public access, but in its testing of the value of Vitruvius’ preparations in a wet, cold environment and whether his treatise would likely have been used outside of a Roman context. In the first episode, viewers watch the mortar mixture, prepared to Vitruvius’ specifications exactly, refuse to set, even over the course of three days due to the moisture levels in British air. The plaster according to Vitruvius was also not compatible with the atmosphere of Wroxeter, cracking in the cold wet of winter shortly after construction completed. The construction methods used in the house were so inappropriate, in fact, that English Heritage has found the cost of repairs and maintenance to be burdensome.[21] This suggests that Romano-British villa owners either set aside funds for continual maintenance or that Roman building practices weren’t translated directly to provincial construction sites, instead depending upon local materials and local building practices in an adapted architectural form.

While not valuable in best understanding Romano-British construction methods, the villa model’s final form does hold value in understanding Roman construction methods, thanks to the room in the villa deliberately left only partially finished (fig. 9). Visitors are able to better understand what’s going on underneath the plaster and floors, creating a more nuanced understanding of the site than what would have been possible from the empty, sterile rooms in the rest of the villa’s reconstruction.

Digital reconstructions

Model 1: partially immersive digital model of the house of Caecilius Iucundus

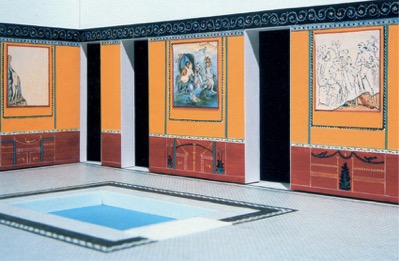

The Swedish Pompeii Project of The Swedish Institute in Rome began in 2000, conceived of as a means of preserving Pompeii’s archaeological evidence through documentation (fig. 10).[22] The team took extensive photographs and laser scans of one of the city’s districts and eventually used the ones they took of the house of Caecilius Iucundus to model a 3-D reconstruction of the villa in video form.[23] By directing the viewer through a realistic rendering of the space with household objects, natural lighting and movement, the model serves to visually immerse the viewer in the environment, creating a sense of being transported back in time. While this is a dangerous means of communicating interpretation, as it suggests to the viewer that it is fact, the designers combat that uncritical acceptance by starting the video with narration and by rendering the villa in its current state and then melding the atrium view into the fully decorated pre-79 AD version of the model (fig 11). They also filmed an accompanying video in which they describe the project and the idea of displaying interpretation in a responsible way within the model.[24] This approach to revealing what’s ‘behind the curtain’ allows the model to be didactically useful, communicating the audience that a model really is just a model while still making a convincing argument for how the atmosphere of the villa may have felt under various environmental conditions. It is a model that creates a realistic atmosphere, though not entirely immersive, since the sounds, smells and living creatures are not included, nor can you control your own movement through the space.

Though in process and not contained in this model, the Swedish researchers also discovered means of interpreting social hierarchies based upon their study of water and sewer systems. With this information at hand, this project has the potential to make one of the first realistic attempts at modeling how different kinds of people moved through the home and the neighborhood, which would be invaluable for improving the repopulation of ancient sites. Thus, the model as it stands currently holds value for villa research in its detailed preservation of the site as it stood in 2000-2010 and its mindfulness about how the environment would have reacted to weather.

Model 2: fully immersive digital model of Pompeii and its houses in Digital Pompeii

The Digital Pompeii Project, sponsored by the University of Arkansas, stands as a contemporary equivalent of Giuseppe Fiorelli’s early cork model of Pompeii’s archaeological digs in its ambition and intention, if not its medium. Directed by professor David Fredrick, the project intends to create a “comprehensive database for visual art and material culture at Pompeii” that supports the 3-D gaming-style model of the entirety of Pompeii.[25] The database will be fully indexed, searchable, and linked to the model’s reproduction of the desired object or building. By adding to the model’s in-game information with the collaborative virtues of networked data, the model has the potential to serve all audiences’ needs, acting a teaching tool for those exploring the homes, serving as a surrogate to physical travel, and increasing the scholarly manipulation of city, which can test new and old assumption with the archaeological evidence.

Within the model’s interface, users can direct their avatar up to point of interest, which will prompt a popup with “descriptions of the wall painting, the myths that it contains, and of the social aspects of why this painting is in this particular room.”[26] This function keeps the viewer aware that this fully immersive environment is evidence-based, but still a model. Though still in development and thus not operational at the moment, the team produced a video describing the process of compiling the visualization data, providing glimpses of how the game-play function will operate, and explaining the risks of the model.[27] To produce the visualization, the team compiled “400 hundred years worth of drawings, etchings, paintings and photographs of Pompeii,” on top of taking their own scans of the site.[28] This process of bringing all of that visual data together into one model ensures a balance of evidence that also documents and renders the current archaeological record of the visual and archaeological evidence up to the present day. As Christopher Johanson notes in his article “Visualizing History: Modeling in the Eternal City,” one of the fundamentally important aspects of digital reconstructions is that they can propose solutions to gaps in the archaeological record.[29] By presenting the archaeological record as it stands, Digital Pompeii allows others to fill in the gaps using the model and the accompanying database in relation to future scholarship.

Conclusion

As Bergmann points out in her article on “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” “[s]cholarly investigation of the ancient interior is like a memory system in that we attach out ideas about Roman culture to its spaces and contents using the methods of labeling and matching.”[30] Models provide the literal house in which researchers can compile their investigative findings and compare them to surrounding evidence. If something does not match, then it must be investigated further to discover where the discrepancy is occurring, in the researcher’s understanding of the archaeological evidence or in the accuracy of the supporting evidence and supposition. From the point of the viewer, a model is mediated means of investigating a home. While the model’s medium and formatting choices can dictate their interaction with the space, they can benefit from the coming together of the information with which the researchers were working. While imperfect for both parties, models, as Box suggested, do supply useful information even as they are imperfect. As this paper suggests, scholarship and public knowledge on the Roman house have benefitted and will benefit from the continued use of models as a tool for research, documentation, and communication.

Images

Bibliography

Bergmann, Bettina. “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 76, no. 2, June 1994.

Blix, Gӧran. From Paris to Pompeii: French Romanticism and the Cultural Politics of Archaeology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

Box, George E., J. Stuart Hunter, and William Hunter. Statistics for Experimenters: Design, Innovation, and Discovery. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Inter-science, 2005.

Burke, John. Life in the Villa on Roman Britain. London, UK: B.T. Batsford, 1978.

Davis, Michael T. “Evidence and Invention: Reconstructing the Franciscan Convent and the College of Navarre in Paris.” Paper presented at Apps, Maps & Models: Digital Pedagogy and Research in Art History, Archaeology & Visual Studies symposium, Duke University, North Carolina, 22 February 2016.

“Digital Pompeii.” University of Arkansas YouTube channel, 12 April 2010.

“Digital Pompeii Home.” Digital Pompeii Project. University of Arkansas, 2011.

Dockrill, Peter. “This reconstructed 3D home reveals ancient Pompeii before Vesuvius struck.” Science Alert, 5 October 2016.

Houses and Monuments of Pompeii: The works of Fausto and Felice Niccolini. Ed. Mark Greenberg. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002.

Johanson, Christopher. “Visualizing History: Modeling in the Eternal City.” Visual Resources, vol. 25, no. 4, 1 December 2009.

Mau, August. “The Pompeian House.” Pompeii: Its Life and Art. New York: Macmillan Company, 1907.

Nevett, Lisa C. “Seeking the domus behind the dominus in Roman Pompeii: artifact disributions as evidence for the carious social groups.” Domestic Space in Classical Antinquity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

“Researchers reconstruct house in ancient Pompeii using 3D technology.” Lund University. 29 October 2016.

Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day. Channel 4 TV, London, UK, 2010.

Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. “Reading the Roman House,” Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

The Swedish Pompeii Project. Swedish Research Council, 2016.

[1] George E. Box, J. Stuart Hunter, and William Hunter, Statistics for Experimenters: Design, Innovation, and Discovery, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Inter-science, 2005), 440.

[2] Michael T. Davis, “Evidence and Invention: Reconstructing the Franciscan Convent and the College of Navarre in Paris,” paper presented at Apps, Maps & Models: Digital Pedagogy and Research in Art History, Archaeology & Visual Studies symposium, Duke University, North Carolina, 22 February 2016. All transcriptions of the video recording of this symposium are my own.

[3] In his paper, Davis acknowledged that while scholars of more modern history find modeling less necessary due to the higher volume of intact architecture, there is value in building these models for all of archaeology, both as investigative scholarship and as teaching tools.

[4] For an impression of present day British attitudes towards historical portrayal and its own history, see Andrew Thomson, “Afterward: The Imprint of the Empire” in Britain’s Experience of Empire in the Twentieth Century, edited by Andrew Thomas (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 330-335; Kate Connolly, “Britain’s view of its history ‘dangerous,’ says former museum director,” The Guardian, 7 October 2016; and even the way Britons’ take their holiday according to ABTA Ltd., Holiday Habits Report 2016 (London, UK: ABTA Ltd., 2016).

[5] John Burke, Life in the Villa on Roman Britain (London, UK: B.T. Batsford, 1978), 35; 40-41.

[6] Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, “Reading the Roman House,” Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 11.

[7] Lisa C. Nevett, “Seeking the domus behind the dominus in Roman Pompeii: artifact disributions as evidence for the carious social groups,” Domestic Space in Classical Antinquity (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 114-118; and Bettina Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 76, no. 2, June 1994, 227.

[8] Stefano de Caro, “Introduction,” Houses and Monuments of Pompeii: The works of Fausto and Felice Niccolini, (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002), 6.

[9] Roberto Cassanelli, “Images of Pompeii: From Engraving to Photography,” Houses and Monuments of Pompeii: The works of Fausto and Felice Niccolini, (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002), 48-49.

[10] August Mau, “The Pompeian House,” Pompeii: Its Life and Art (New York: Macmillan Company, 1907), 245.

[11] Gӧran Blix, From Paris to Pompeii: French Romanticism and the Cultural Politics of Archaeology (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), p 209-213.

[12] Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” 228.

[13] Ibid., 227.

[14] Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” 226-227.

[15] Ibid., 230-231.

[16] Ibid., 237.

[17] Ibid., 237.

[18] Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” 241-246.

[19] “Episode 1,” Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day, Channel 4 TV, London, UK, 2010.

[20] John Burke, Life in the Villa in Roman Britain (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1978), 32.

[21] “Wroxeter Roman Villa,” English Heritage.

[22] “Welcome to the Swedish Pompeii Project,” The Swedish Pompeii Project, 2016.

[23] “Researchers reconstruct house in ancient Pompeii using 3D technology,” Lund University, 29 October 2016.

[24] Peter Dockrill, “This reconstructed 3D home reveals ancient Pompeii before Vesuvius struck,” Science Alert, 5 October 2016.

[25] “Digital Pompeii Home,” Digital Pompeii Project, University of Arkansas, 2011.

[26] “Digital Pompeii,” University of Arkansas YouTube channel, 12 April 2010.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Christopher Johanson, “Visualizing History: Modeling in the Eternal City,” Visual Resources, vol. 25, no. 4, 1 December 2009, 403-404, 413-414.

[30] Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” 226.