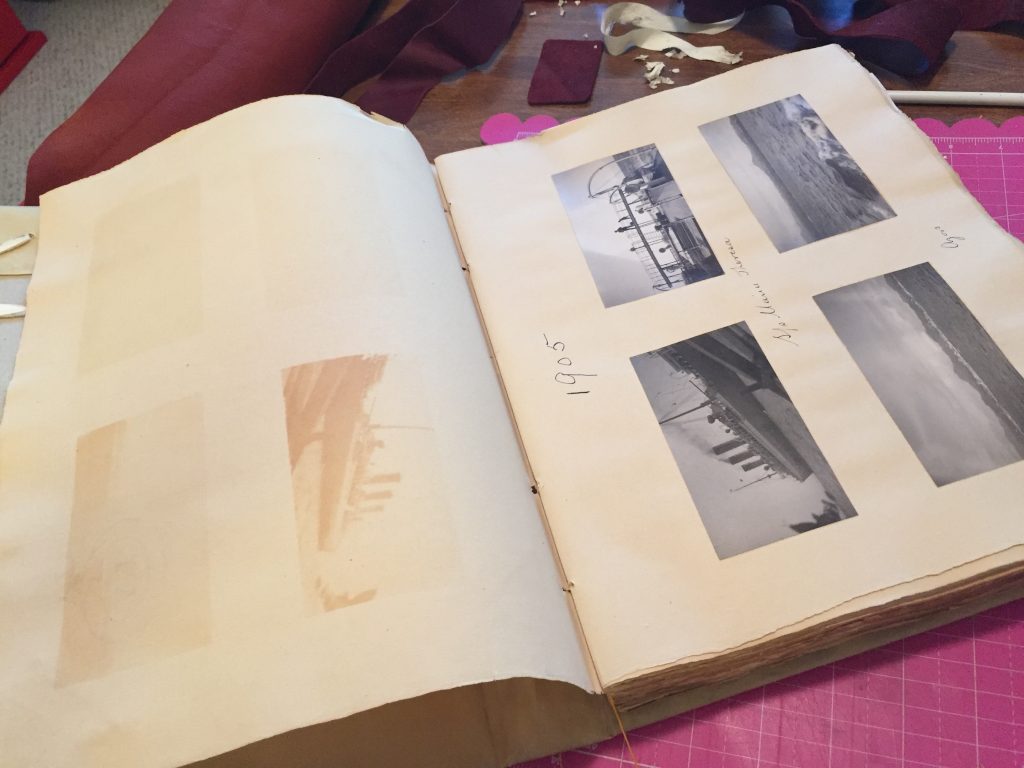

One day while I was working at the Grogan & Co. Auctioneers, a stunning pair of Grand Tour photo albums appeared in the glass cases in the entry showroom. These handbound, illuminated albums came without provenance and in grimy, dilapidated condition. I was immediately entranced and bookended every workday by pouring over the early twentieth century pictures of Algiers and cities all over Italy that were gradually transferring perfect mirror images to the facing pages as age degraded the prints. Investigating possible binderies and unearthing a likely provenance became my lunchtime pet topic. The only clues were the date of the albums and the first initial, surname and city of the cover illuminator. While I learned quite a bit about the Grand Tour—which was a tour of northern Africa and Western Europe that proved highly popular among the American moneyed classes of the nineteenth century, petering out in popularity into the early twentieth century—I never did uncover information about the albums’ creation or the individuals taking and photographing their tour in 1905.

To indulge my minor obsession and thank me for my time with them, my bosses decided to gift me with one of the albums at my going away party. I was overjoyed to provide a loving home to the album (even as the archivist in me was sighing contrarily over the separation of the two books). I was especially excited to get to try my hand at preservation. The thread holding together the album’s long stitch binding was breaking into pieces and slowly releasing the gatherings from their binding, and the covers, leather spine backing and leather tie were all filthy, with both leather items flaking apart. And then, as mentioned, the photos were transferring onto their facing pages. This year, I finally got around to applying the conservation principles from school to the album.

The conservation process

Within conservation, experts fall on a sliding scale between two extremes: (1) stabilizing the item in its current state so that it stops degrading, treating the current state as the desired on; and (2) intervening in such a way that the item is restored to a chosen theoretical previous iteration, such as ‘like new’ or ‘x decades after creation.’ As an archivist rather than a conservator and as a social art historian with a focus on material cultures, I tend to privilege the first principle over the second in honor of the life of the object; however, with this project, the two vied with one another in the album’s multiple preservation needs. For images of the album as it progressed through conservation, see the final section of this post.

Stabilizing the photographs

Photographs are one of the most complicated items for preservation (surpassed only by film and other acetate recording tapes). Each type of print method within photography requires a slightly different intervention and storage system, and while I know very little about stabilizing photo prints, I do know that the acidity in paper can dramatically hasten the process of image transfer and assorted other degradation. The paper used for the album, while a decent laid paper, was produced well before ‘acid-free’ was a deliberate and widely produced commodity, and the paste used to secure the photographs to the page, the same. That the paper contains acid meant that ideal preservation conditions for the photos demanded the removal of the photographs and their storage in a humidity and temperature controlled environment in Mylar sleeves. Removing them, however, would destroy the experience of the viewer, leaving them with a stunning cover and page upon page covered with nothing but the remnant markings of glue and the transferred images.

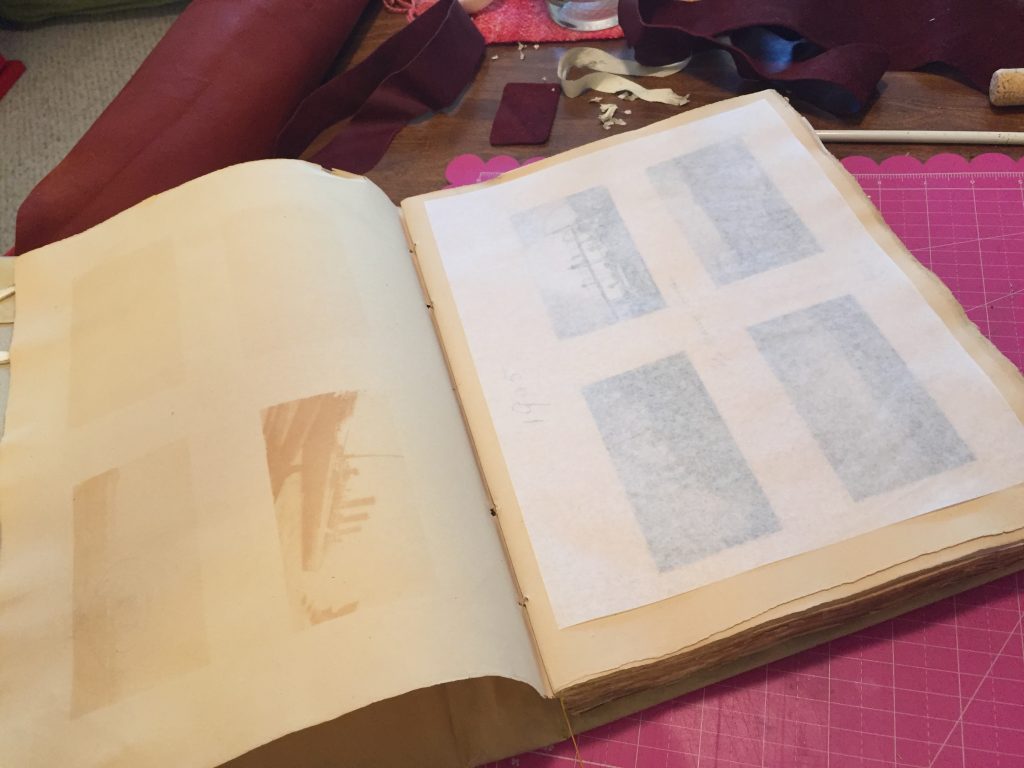

While these ghostly images are compelling in themselves, I wanted to keep the album intact as much as possible. In order to maintain that while preventing as much further transfer as possible, I inserted acid free tissue sheets between each page, hoping that removing contact between the front of the prints and the acidic pages across from them would be enough to stabilize them for at least the next decade. In this instance, I chose a minor and (debatably) less desirable preservation intervention in order to privilege the first priority of keeping the item as close to its current state as possible so that user experience is maintained.

Stabilizing the binding

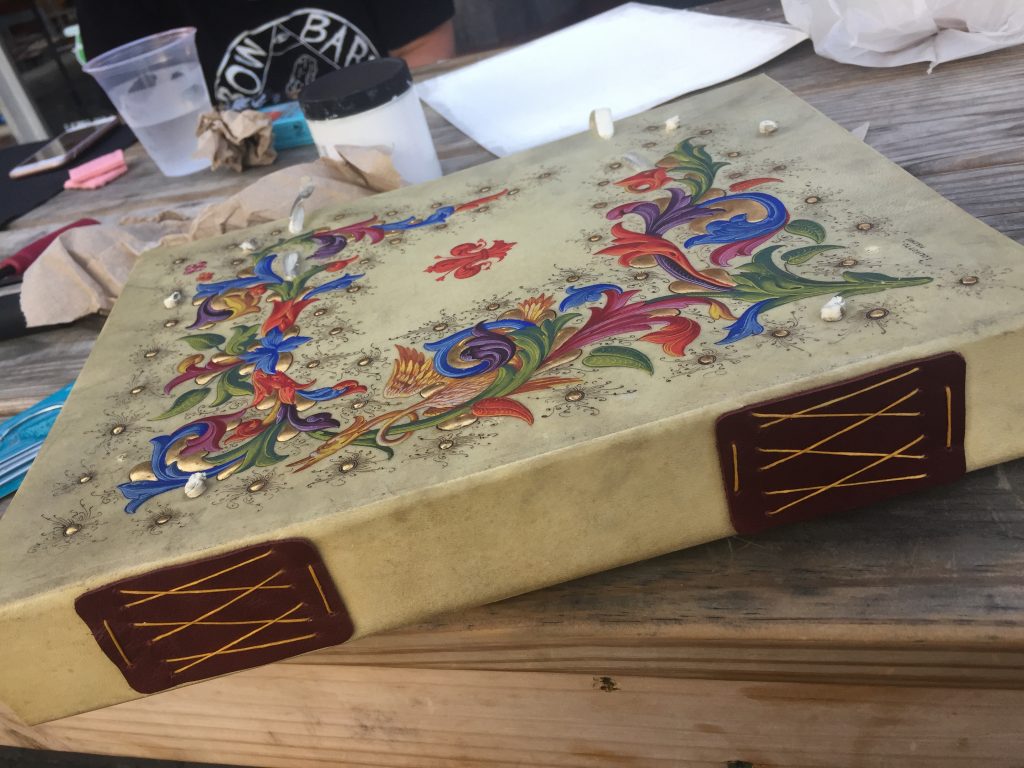

With the binding, I chose to privilege the second principle of returning the object to an earlier iteration, one in which the binding was intact and the pages could be safely perused. Again, this choice was informed by the desire to make the user experience as close to the intended use of the object as possible. Luckily, enough of the thread securing the quires to the spine were intact for me to understand the stitching pattern of the original long stitch binding. After cleaning the covers of the debris of time and removing the remnants of the remaining thread, I cut new rectangles of similarly colored leather and punched threading holes that matched the original thread backing. Though the original thread appeared to have originally be white, I used a rich yellow linen thread that matched more closely the color of the original thread as it appeared after over a century of existence. I followed the same threading pattern that I worked out from what was left of the thread, keeping a medium tension so that the quires are stable but the movement of turning the pages won’t increase the tearing that has gradually occurred around the binding holes in the center of each quire.

The closures

The two ties knotted into the covers made of alum tawed leather strips I left alone. They are heavily integrated into the covers due the the multiple securing knots, so while one of the strips on the front cover has torn away entirely and the others are degrading, I chose not to replace them with new strips of leather to create a functional closure. I made this choice because the closure is not vital to the structure of the book; it would have been inconsistent in principle to make an unnecessary alteration to the book’s structure. If the knots in the cover end up doing further damage, even without pressure being put on the ties by using them to keep the album closed, then I will replace the ties. But for now, they will remain intact and untouched beyond the gentle removal of grime I performed on the whole book.

Process photos