Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.

— George Box and Norman Draper, Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces, 1987

Introduction

Statistician George Box was a man with a conditional love of models. He maintained that, while simple models can approximate reality, no model could entirely represent the real world exactly. Despite this inability, Box did allow that a model could “supply a useful approximation to reality,” rendering it a handy tool.[1] It is with this wary consideration in mind that I investigate how modeling methods influence our understanding of Roman villas.

Architectural models are useful tools in that they enable scholars to better understand their research subject and allow members of the public to better engage with their cultural history. As Mount Holyoke professor Michael T. Davis shared in his presentation at Duke University’s 2016 digital humanities symposium, “we, as a species, tend towards a stubborn positivism, demanding sensory and—I think, above all—visual confirmation as the means by which we, in the words of Thomas Aquinas, “gather the intelligible truths of all things.”’[2] Interacting with a visual model can bring history to life for schoolchildren, inspiring greater investment in local communities, in a school subject or in a career path. For historians, building a visual model can test literary and archaeological evidence against the realities of gravity, humidity, time of day or year, and sight lines, among other physical restrictions to reconstruct what was probable in the construction or arrangement of a building.

From 19th and 20th century to present day rediscoveries sites, Roman buildings have proved a rich area for modeling projects. Since they typically survive as limited remains or as wonders that dominant scholarship decided should concern the world at large, researchers required a means of compiling their observations into a cohesive and observable form for their peers, resulting in that sensory, visual confirmation of a model, as Davis mentioned.[3] Sites such as Pompeii have proved especially fruitful, given the relative volume of preserved evidence unmediated by further societal interventions until its mid-eighteenth century rediscovery, enshrining the site in the collective archaeological imagination. But locations with fewer intact architectural and material remains, such as the United Kingdom, have also inspired interest in reconstruction. When first approaching this paper, I planned to direct my geographic focus to models of Romano-British villas, since Britain maintains such visible enthusiasm for reliving its glorious history.[4] However, between limited interest in digital reconstruction of these numerous villa sites, the departure of the provincial architecture from its Italian counterparts, and the democratic audience targeted by Britain’s physical modeling projects, such a scope proved too limiting. Consequently, this study includes models of villas from both Pompeii and from Britannia.

Villas are particularly interesting sites to reconstruct, since Roman home structures tended to be locations that fluidly melded the public and private spheres as we now understand them. For instance, villas of Britannia were often part of a larger farming estate that would adjoin granaries and also acted as the place where the dominus would conduct business and shelter the household.[5] Pompeian villas operated similarly, with fluidity between public business and private domesticity.[6] Until recently, scholars set out to uncover the fixed purpose of a room, but with the holistic incorporation of anthropology, archaeology and social art history into both written scholarship and models, that pattern has shifted towards a greater emphasis on letting the evidence on the ground speak for itself, encouraging scholars to draw conclusions from the evidence rather than theory.[7] Reconstruction models help scholars experience the evidence sensorially to uncover the otherwise unforeseen in the most likely mundane realities of life within these villas. Investigating villas provides human connection not just for scholarship, but also for average citizens, as well, allowing them to envision themselves in these histories so to bridge the relevancies of the past and the present.

History of models as a means of reconstruction

Before digging into the villa models specifically, however, I first wish to progress quickly through the evolution of archaeological architectural models and how the conversation around models has remained relatively static, despite the extended time frame and shifting media. As Stefano de Caro recounts in his introduction to the 2002 book Houses and Monuments of Pompeii: The works of Fausto and Felice Niccolini, “[a]t the very moment that creating a “virtual” Pompeii in the interest of conserving the ancient city has been put forward, here is an opportunity to present Le case ed i monumenti [(originally published 1854)], which in its own way was the first virtual Pompeii.”[8] Clearly the discussion around models persists unabated.

With the early-nineteenth century growth of archaeology as a discipline and an increasing cultural concern with the scientific, models became a pressing preoccupation. As Roberto Cassanelli describes in his essay on “Images of Pompeii: From Engraving to Photography,” the early forms those models took included both traditional modes of representation—sketches, watercolors, gouache paintings, lithographs and engravings, and ground plans—as well as developing technologies—photography in the form of daguerreotype and collotypes.[9] While not models in the sense of allowing the viewer to sensuously interact with and imagine the space, these two-dimensional renderings opened the discussion ongoing in modeling projects to present day, specifically the debates over whether a model is a greater reflection of the perspectives of the modern culture than the realities of the ancient evidence and whether a model is more dangerous than useful, as it can take on a life of its own by creating a sense of certainty that disregards the nuances of historical evidence and educated conjecture.

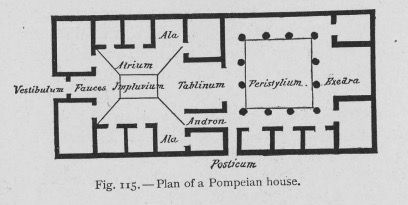

August’s Mau’s model of the ideal Pompeian home from his book Pompeii: Its Life and Art captures both issues beautifully. He begins the chapter on Pompeian houses by acknowledging how source material on domestic architecture in Italy is limited to Vitruvius’ treatise De architectura and the remains of Pompeii itself. He goes on to provide his conclusion that, despite “many variations from the plan described by the Roman architect [Vitruvius]”—Pompeian houses should still be understood to be in accordance with the treatise’s particulars.[10] After proving his general findings on the houses of the city, he supplies the reader with this ground plan model for the Pompeian house (fig. 1). This ground plan has taken on a life of its own, taught in survey courses and introductions to Pompeii across the United States with minimal intervention complicating the reading of it so as to be useful for general study, but neglects to problematize which evidences are privileged in model creation. In this case, Mau showed deference for the literary evidence rather than allowing the archaeological evidence to guide the design, which is not made clear when taking the model out of its context within the chapter, as it so often is. That preference for privileging the textual evidence also has little to do with the quality of the evidence available in Pompeii and everything to do with the way that scholarship was conducted during Mau’s time.

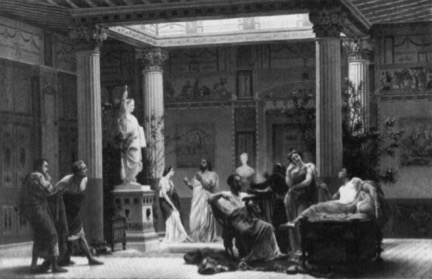

Prince Napoleon III’s Pompeian mansion reconstruction is even more reflective of the early conversations around models being more reflective of their own time than the archaeological reality. The prince’s architects modeled the palace on Pompeian villas such as that of Diomedes and the House of Pansa. The court received the reconstruction as “a rigorous restitution, … a deeply learned archaeological treatise written in stone that can be inhabited,” while also believing it “to be a symbolic expression for a modern imperial lifestyle…[that held] up a polished patrician mirror.”[11] This palatial model acted as a lens for present day concerns, not reconstruction for the sake of understanding the archaeological past. The model suited, instead, the repopulating of the Roman past with contemporary concerns and behavior, as is evident in Boulanger’s painting of a rehearsal in which the friends of the prince combine “archaeology and fiction…[by] emulate[ing] what they imagined to have been a Pompeian life of elegant leisure” (fig. 2).[12] In this case, all historical integrity is lost due to the nature of the reconstruction serving as a playhouse rather than as a true model.

The debates around how models mediate our understanding of the sites they reconstruct continue regardless of the evolution in media for reconstruction, moving through physical small-scale models, large-scale reconstructions, 3-D computer assisted drafting, visually immersive 3-D video, fully immersive 3-D gaming technology, and artificial reality.

Physical reconstructions

Model 1: physical, small-scale model of the House of the Tragic Poet

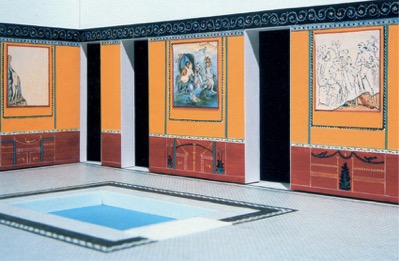

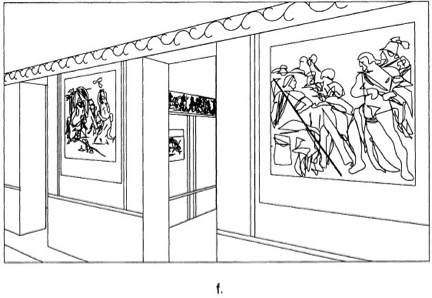

The second century BC House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii has received significant attention from archaeologists for its apparent agreement with Vitruvius’ observations in De architectura on the properly arranged and proportioned home.[13] As part of that attention, a number of models have been constructed of it. The small-scale physical model Bettina Bergmann uses in her article on “The Roman House as Memory Theater” (fig. 3-4) is particularly relevant to an investigation of how models are and are not useful in expanding knowledge of the Roman villa. She uses the model in conjunction with another computer assisted line-drawing reconstruction (fig. 5) to recontextualize the conception of the house and its decoration so that it prioritizes the likely realities of viewing and moving through the environment, as supported primarily by the archaeological record and then performed.[14]

Throughout the paper, she uses the physical reconstruction supported by the computer assisted line drawing model to draw conclusions about the strength of previous and contemporary scholars’ supposition regarding how the villa acted “as a frame for action” within the assumed social structures of private and public. Of these model-supported conclusions, she feels confident confirming the idea of the axes of private and public social differentiation based on the sight lines and wall painting indicators.[15] The model also allowed her to recontextualize the wall paintings, as they were removed from the villa and now reside in the Naples Museum in an order imposed by the institution. By drawing on the artistic rendering of the wall paintings within the rooms by archaeologists who experienced the villa after its rediscovery and before it decorative deconstruction.[16] Based on the finding of the wall painting series, Bergmann’s model undermines the traditional view of the House of the Tragic Poet as a “Homeric house,” since the order of the wall paintings does not suggest a cohesive, linear story of the Iliad being performed.[17] Instead, Bergmann suggests a new conception of the artist, one that gives them agency and credit not only their formal skills, but also their dialectic, analytical skills to create panels that were “composed in relation to each other and for th[e] space” based on repeated and responsive compositional choices that only become obvious when examined on the walls in their original order in the reconstruction and restoration enabled by the model.[18]

While Bergmann’s article provides a strong argument for the value of models as a scholarly tool in uncovering and testing theory on the Roman villa, neither argument nor model is without its flaws. The desire to repopulate the model with a figure is misleading, as the visual of a lone figure in the space leads one to believe that it might have been the wall paintings alone that directed traffic through the house, instead of other people, such as slaves. The model also misleads in the gallery-quality emptiness of the rooms. As is evident in model 1 of the digital reconstruction in the next section, having objects in the space entirely alters the way that a viewer might progress through the rooms or interact with the wall paintings, since they’re partially obscured. The model leads to the treatment of the Roman villa as a painting gallery, rather than a lived-in space.

Model 2: physical, large-scale model of the villa at Wroxeter

Full-scale physical models pose a different set of virtues and problems. The villa reconstruction at Wroxeter, England is one such model (fig. 6-7). The villa itself, a hybrid of the winged-corridor and courtyard villas common to Britannia (fig. 8), was located near the significant Roman settlement of Viroconium (now Wroxeter), a bustling city center and legion encampment, rediscovered in 1859. In 2010, English Heritage took on the project of reconstructing the villa to scale using ancient Roman building methods under the direction of Chester University’s professor Dai Morgan Evans. Channel 4 TV supported the effort in exchange for the building of the model to be made into a television program, “Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day.”[19] While campy and rife with reality television distractions, the program was able to convey the value in testing the literary evidence against the reality of regional environments far from Rome.

Professor Morgan Evans decided to use Vitruvius’ treatise on architecture as the primary guide for how to construct the house, despite British patterns of adapting what immigrants bring to the demands and habits of the region and the fundamental differences in architectural arrangement in the Roman atrium house and the Romano-British villa counterparts.[20] Due to this decision, as well as the lack of household objects and accompanying texts on the finalized site, the model’s value lies not in its final state or public access, but in its testing of the value of Vitruvius’ preparations in a wet, cold environment and whether his treatise would likely have been used outside of a Roman context. In the first episode, viewers watch the mortar mixture, prepared to Vitruvius’ specifications exactly, refuse to set, even over the course of three days due to the moisture levels in British air. The plaster according to Vitruvius was also not compatible with the atmosphere of Wroxeter, cracking in the cold wet of winter shortly after construction completed. The construction methods used in the house were so inappropriate, in fact, that English Heritage has found the cost of repairs and maintenance to be burdensome.[21] This suggests that Romano-British villa owners either set aside funds for continual maintenance or that Roman building practices weren’t translated directly to provincial construction sites, instead depending upon local materials and local building practices in an adapted architectural form.

While not valuable in best understanding Romano-British construction methods, the villa model’s final form does hold value in understanding Roman construction methods, thanks to the room in the villa deliberately left only partially finished (fig. 9). Visitors are able to better understand what’s going on underneath the plaster and floors, creating a more nuanced understanding of the site than what would have been possible from the empty, sterile rooms in the rest of the villa’s reconstruction.

Digital reconstructions

Model 1: partially immersive digital model of the house of Caecilius Iucundus

The Swedish Pompeii Project of The Swedish Institute in Rome began in 2000, conceived of as a means of preserving Pompeii’s archaeological evidence through documentation (fig. 10).[22] The team took extensive photographs and laser scans of one of the city’s districts and eventually used the ones they took of the house of Caecilius Iucundus to model a 3-D reconstruction of the villa in video form.[23] By directing the viewer through a realistic rendering of the space with household objects, natural lighting and movement, the model serves to visually immerse the viewer in the environment, creating a sense of being transported back in time. While this is a dangerous means of communicating interpretation, as it suggests to the viewer that it is fact, the designers combat that uncritical acceptance by starting the video with narration and by rendering the villa in its current state and then melding the atrium view into the fully decorated pre-79 AD version of the model (fig 11). They also filmed an accompanying video in which they describe the project and the idea of displaying interpretation in a responsible way within the model.[24] This approach to revealing what’s ‘behind the curtain’ allows the model to be didactically useful, communicating the audience that a model really is just a model while still making a convincing argument for how the atmosphere of the villa may have felt under various environmental conditions. It is a model that creates a realistic atmosphere, though not entirely immersive, since the sounds, smells and living creatures are not included, nor can you control your own movement through the space.

Though in process and not contained in this model, the Swedish researchers also discovered means of interpreting social hierarchies based upon their study of water and sewer systems. With this information at hand, this project has the potential to make one of the first realistic attempts at modeling how different kinds of people moved through the home and the neighborhood, which would be invaluable for improving the repopulation of ancient sites. Thus, the model as it stands currently holds value for villa research in its detailed preservation of the site as it stood in 2000-2010 and its mindfulness about how the environment would have reacted to weather.

Model 2: fully immersive digital model of Pompeii and its houses in Digital Pompeii

The Digital Pompeii Project, sponsored by the University of Arkansas, stands as a contemporary equivalent of Giuseppe Fiorelli’s early cork model of Pompeii’s archaeological digs in its ambition and intention, if not its medium. Directed by professor David Fredrick, the project intends to create a “comprehensive database for visual art and material culture at Pompeii” that supports the 3-D gaming-style model of the entirety of Pompeii.[25] The database will be fully indexed, searchable, and linked to the model’s reproduction of the desired object or building. By adding to the model’s in-game information with the collaborative virtues of networked data, the model has the potential to serve all audiences’ needs, acting a teaching tool for those exploring the homes, serving as a surrogate to physical travel, and increasing the scholarly manipulation of city, which can test new and old assumption with the archaeological evidence.

Within the model’s interface, users can direct their avatar up to point of interest, which will prompt a popup with “descriptions of the wall painting, the myths that it contains, and of the social aspects of why this painting is in this particular room.”[26] This function keeps the viewer aware that this fully immersive environment is evidence-based, but still a model. Though still in development and thus not operational at the moment, the team produced a video describing the process of compiling the visualization data, providing glimpses of how the game-play function will operate, and explaining the risks of the model.[27] To produce the visualization, the team compiled “400 hundred years worth of drawings, etchings, paintings and photographs of Pompeii,” on top of taking their own scans of the site.[28] This process of bringing all of that visual data together into one model ensures a balance of evidence that also documents and renders the current archaeological record of the visual and archaeological evidence up to the present day. As Christopher Johanson notes in his article “Visualizing History: Modeling in the Eternal City,” one of the fundamentally important aspects of digital reconstructions is that they can propose solutions to gaps in the archaeological record.[29] By presenting the archaeological record as it stands, Digital Pompeii allows others to fill in the gaps using the model and the accompanying database in relation to future scholarship.

Conclusion

As Bergmann points out in her article on “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” “[s]cholarly investigation of the ancient interior is like a memory system in that we attach out ideas about Roman culture to its spaces and contents using the methods of labeling and matching.”[30] Models provide the literal house in which researchers can compile their investigative findings and compare them to surrounding evidence. If something does not match, then it must be investigated further to discover where the discrepancy is occurring, in the researcher’s understanding of the archaeological evidence or in the accuracy of the supporting evidence and supposition. From the point of the viewer, a model is mediated means of investigating a home. While the model’s medium and formatting choices can dictate their interaction with the space, they can benefit from the coming together of the information with which the researchers were working. While imperfect for both parties, models, as Box suggested, do supply useful information even as they are imperfect. As this paper suggests, scholarship and public knowledge on the Roman house have benefitted and will benefit from the continued use of models as a tool for research, documentation, and communication.

Images

Bibliography

Bergmann, Bettina. “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 76, no. 2, June 1994.

Blix, Gӧran. From Paris to Pompeii: French Romanticism and the Cultural Politics of Archaeology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

Box, George E., J. Stuart Hunter, and William Hunter. Statistics for Experimenters: Design, Innovation, and Discovery. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Inter-science, 2005.

Burke, John. Life in the Villa on Roman Britain. London, UK: B.T. Batsford, 1978.

Davis, Michael T. “Evidence and Invention: Reconstructing the Franciscan Convent and the College of Navarre in Paris.” Paper presented at Apps, Maps & Models: Digital Pedagogy and Research in Art History, Archaeology & Visual Studies symposium, Duke University, North Carolina, 22 February 2016.

“Digital Pompeii.” University of Arkansas YouTube channel, 12 April 2010.

“Digital Pompeii Home.” Digital Pompeii Project. University of Arkansas, 2011.

Dockrill, Peter. “This reconstructed 3D home reveals ancient Pompeii before Vesuvius struck.” Science Alert, 5 October 2016.

Houses and Monuments of Pompeii: The works of Fausto and Felice Niccolini. Ed. Mark Greenberg. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002.

Johanson, Christopher. “Visualizing History: Modeling in the Eternal City.” Visual Resources, vol. 25, no. 4, 1 December 2009.

Mau, August. “The Pompeian House.” Pompeii: Its Life and Art. New York: Macmillan Company, 1907.

Nevett, Lisa C. “Seeking the domus behind the dominus in Roman Pompeii: artifact disributions as evidence for the carious social groups.” Domestic Space in Classical Antinquity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

“Researchers reconstruct house in ancient Pompeii using 3D technology.” Lund University. 29 October 2016.

Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day. Channel 4 TV, London, UK, 2010.

Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. “Reading the Roman House,” Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

The Swedish Pompeii Project. Swedish Research Council, 2016.

[1] George E. Box, J. Stuart Hunter, and William Hunter, Statistics for Experimenters: Design, Innovation, and Discovery, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Inter-science, 2005), 440.

[2] Michael T. Davis, “Evidence and Invention: Reconstructing the Franciscan Convent and the College of Navarre in Paris,” paper presented at Apps, Maps & Models: Digital Pedagogy and Research in Art History, Archaeology & Visual Studies symposium, Duke University, North Carolina, 22 February 2016. All transcriptions of the video recording of this symposium are my own.

[3] In his paper, Davis acknowledged that while scholars of more modern history find modeling less necessary due to the higher volume of intact architecture, there is value in building these models for all of archaeology, both as investigative scholarship and as teaching tools.

[4] For an impression of present day British attitudes towards historical portrayal and its own history, see Andrew Thomson, “Afterward: The Imprint of the Empire” in Britain’s Experience of Empire in the Twentieth Century, edited by Andrew Thomas (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 330-335; Kate Connolly, “Britain’s view of its history ‘dangerous,’ says former museum director,” The Guardian, 7 October 2016; and even the way Britons’ take their holiday according to ABTA Ltd., Holiday Habits Report 2016 (London, UK: ABTA Ltd., 2016).

[5] John Burke, Life in the Villa on Roman Britain (London, UK: B.T. Batsford, 1978), 35; 40-41.

[6] Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, “Reading the Roman House,” Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 11.

[7] Lisa C. Nevett, “Seeking the domus behind the dominus in Roman Pompeii: artifact disributions as evidence for the carious social groups,” Domestic Space in Classical Antinquity (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 114-118; and Bettina Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 76, no. 2, June 1994, 227.

[8] Stefano de Caro, “Introduction,” Houses and Monuments of Pompeii: The works of Fausto and Felice Niccolini, (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002), 6.

[9] Roberto Cassanelli, “Images of Pompeii: From Engraving to Photography,” Houses and Monuments of Pompeii: The works of Fausto and Felice Niccolini, (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002), 48-49.

[10] August Mau, “The Pompeian House,” Pompeii: Its Life and Art (New York: Macmillan Company, 1907), 245.

[11] Gӧran Blix, From Paris to Pompeii: French Romanticism and the Cultural Politics of Archaeology (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), p 209-213.

[12] Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” 228.

[13] Ibid., 227.

[14] Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” 226-227.

[15] Ibid., 230-231.

[16] Ibid., 237.

[17] Ibid., 237.

[18] Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” 241-246.

[19] “Episode 1,” Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day, Channel 4 TV, London, UK, 2010.

[20] John Burke, Life in the Villa in Roman Britain (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1978), 32.

[21] “Wroxeter Roman Villa,” English Heritage.

[22] “Welcome to the Swedish Pompeii Project,” The Swedish Pompeii Project, 2016.

[23] “Researchers reconstruct house in ancient Pompeii using 3D technology,” Lund University, 29 October 2016.

[24] Peter Dockrill, “This reconstructed 3D home reveals ancient Pompeii before Vesuvius struck,” Science Alert, 5 October 2016.

[25] “Digital Pompeii Home,” Digital Pompeii Project, University of Arkansas, 2011.

[26] “Digital Pompeii,” University of Arkansas YouTube channel, 12 April 2010.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Christopher Johanson, “Visualizing History: Modeling in the Eternal City,” Visual Resources, vol. 25, no. 4, 1 December 2009, 403-404, 413-414.

[30] Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater,” 226.

]]>What follows is the result of that investigation.

Introduction

Scholarship on the medieval period of what is now Western Europe and the United Kingdom displays a distinct preference for the mid- to late- portion of the period, neglecting history prior to 1100. This is perhaps due to the pre-1100’s comparative lack of clear archaeological and material evidence. Perhaps it is due to the period’s isolation from the Renaissance, the darling of academic imagination and the foundation for our current culture. I posit, however, that the period’s neglect is likely due the modern mind’s inability to fully adopt a “period eye” for pre-literate, temporally distant cultures like those of the early medieval period.[1] Even the way the previous sentence frames the pre-1100s as ‘pre-literate’ privileges a post-Renaissance perspective that resists acknowledging the earlier time on its own terms, preferring instead to understand it in relation to our assumption that literacy is the natural and inevitable path an oral culture must take to be sophisticated. As art theorist Michael Baxandall writes in his essay on the period eye,

one brings to the picture [or any historical materials] a mass of information and assumptions drawn from general experience. Our own culture is close enough to the Quattrocento for us to take a lot of the same things for granted and not have a strong sense of misunderstanding the pictures; we are closer to the Quattrocento mind than to the Byzantine [or early medieval], for instance. This can make it difficult to realize how much our comprehension depends on what we bring to the picture.[2]

But, as historian Brian Stock investigates in his research on the impact of literacy on oral cultures, literacy fundamentally changes the way we understand ourselves, our relationships, and construct and interact within societies.[3] We, as literate people in a literate culture, must set aside the basis of our entire worldview to glimpse the way one in an oral culture might understand reality.

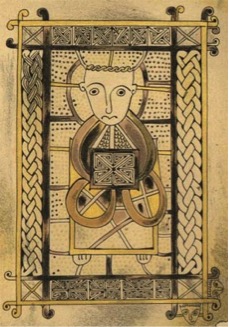

Ireland—the setting of my investigation—was an entirely oral culture until the introduction of Christianity in the early 400s C.E[4] Even with the rapid adoption of Christianity and a growing trust in the written word (upon which the Catholic Church depended for its authority), Ireland remained predominantly oral and illiterate deep into the medieval period, with only a sliver of the upper and the clerical classes boasting full literacy.[5] As such, the texts of early medieval Ireland from 600-900 C.E were primarily Christian, and the Irish scribes developed a distinctly Irish form of religious text in pocket gospels.[6] These gospel books were small, as their name suggests, diminutive in size and weight in order to accommodate a more “intimate, almost private” style of reading and to fit within the tooled and locked leather satchels, called cumdachs, that their monks wore around the neck (fig. 1).[7] Though some of these pocket gospels received additional liturgical passages and accompanying materials later, the standard pocket gospels of the 7th-10th centuries contained only the four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.[8]

Textuality in the early medieval period

Literacy goes far beyond the ability to read words and a preference for written words over aural authority.[9] In the medieval period, literacy existed within a spectrum from complete literacy to complete illiteracy, with most of those outside of complete illiteracy operating within partial literacies. When an oral culture like Ireland’s begins to incorporate the written word into its traditions, the culture is not defined by literacy or illiteracy, but by the “variety and abundance” of collaborations between the two, resulting in what Stock calls a textual culture.[10] Textuality is a more appropriately term than literacy for the early medieval Irish relationship with the written word, since it doesn’t divorce the written word from oral culture’s preference for speaking and hearing. [11] The early introduction of the written word into an oral culture results in a focus on the use of and interaction with text in certain very specific settings, not the ability to read and comprehend written ideas.[12] Instead, the book and paper take on a role in which they are representational containers of authority that serve as objects of use and facilitators of certain experiences. They do not function as texts to be read for direct textual understanding. Or, as Stock puts it, textuality focuses “not [on] what texts are, but what people do with them.”[13] For instance, the presence of a leaf of vellum at the time of an oral land transaction was sufficient to lend the agreement permanent legal authority.[14]

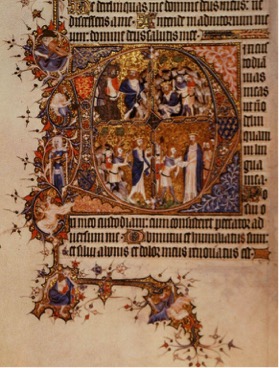

Due to the highly oral nature of the textual culture of early medieval Ireland, it is virtually guaranteed that the owners of these pocket gospels would have had the books’ contents memorized, marking the script and illumination as visual queues rather than as decorated words to be read line by line. David B. Morris adds to this supposition in his essay “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” noting that medieval church readers would have practiced repetition and purposeful memorization to make the gospels familiar and accessible for reflection, even when the text was not legible before them.[15] This is reinforced again by the continued relationship with textuality even two centuries after pocket gospels fell out of fashion; despite the significant move towards a more literate culture by this time, prayer books in the form of books of hours (fig. 2) used image and text as “memory guides for the reader…[that] operated as effective and appropriate cues for contemplation during the recitation of the familiar prayers.”[16] The function of memory in a textual-oral culture still held with the growth of literate culture.

Use of the book as an object

As mentioned previously, the containers for words—both leaves of parchment and books—held power in early medieval Ireland. This power was twofold. Firstly, they acted as a means for the Church to harness non-Christian magical practices and thinking; secondly and relatedly, they acted as objects that gave protection and, thus, deserved protection.

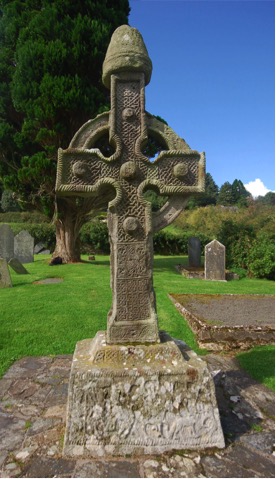

The book acted as a means of translating the Irish magic of power and miracle through the elision of local magical iconography and symbolic functioning, which was part of a larger movement of appropriation sanctioned by Pope Saint Gregory I, holder of the papal seat from 590 to 604 C.E[17] As Valerie I. J. Flint points out in her book The Rise of Magic In Early Medieval Europe, officials nurturing the introduction of Christianity into Ireland regularly borrowed and adapted non-Christian sites, objects and emotional associations with Christian ones, using everything from the placement of Christian sites to iconography on freestanding crosses to accomplish the “peaceful penetration of societies very different from their own.”[18] Like all good salespeople, the clergy framed Christianity as the newest and most effective form of magic to accomplish what the people were already seeking in their non-Christian practices. As the power of the Christian Church lies in its canonical scripture, it follows that it would have a vested interest in impregnating the Bible and other Christian texts with mystical power. Reverence for the power of books would be a natural progression in a textual culture that developed out of a religious context. With books holding the divine magic of the word of God, it follows that books themselves would be revered as magical objects, and the clergy would themselves be honored as those who could provide access to and dispense this power.

In order to further the effort to align Christian texts with non-Christian mysticism, illuminators and those executing other Christian crafts used the local aesthetic vocabulary. Flint notes that

[a]s impressive memories of non-Christian hanging sacrifices, special stones and woods, omens, and supernatural means of healing are carried vividly and carefully into the monuments[, ivories, metalwork, and illuminated manuscripts] proclaiming Christianized and supernatural power at the new shrines then, so too, on a rather smaller scale, are echoes of other forms of supernatural practice, such as amuletic rings and knots, weaving, and binding. All of these, obviously, are to be rendered subordinate to the new ways of invoking the supernatural; yet also they are still to form part of it, where this is possible.[19]

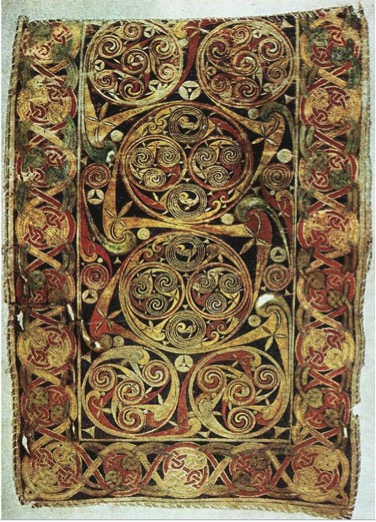

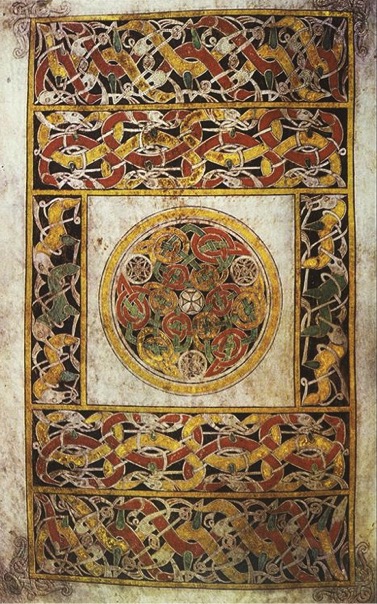

Thus, it is unsurprising that the monkish illuminators would have used the mesmerizing iconography known to the Irish people. The Book of Durrow’s carpet pages (figs. 3 and 4), some of the most famous pages from any of the pocket gospels, provide the perfect opportunity to observe the direct parallels drawn between both carving and metalworking and illumination. Observe how the interlacing, abstracted animals and triskeles in the Book of Durrow pages, the north high cross at Ahenny (figs. 5 and 6) and the Tara brooch (figs. 7 and 8) match so closely. They are drawn directly from the pre-existing Insular art so recognizable to and standardized by the people of Ireland. This iconography would have been associated with status and protection.[20]

The book provided protection and was something that needed protecting. Since the Church had effectively used the attitude of a textual culture towards books to its advantage, the people associated them with magic and all of its associated power. The protective quality lent to these pocket gospels was so enduring that even into the 17th century, the Irish public still viewed them as powerful protective objects; a farmer went so far as to immerse a section in his cattle’s drinking water to cure them of illness.[21] Within the medieval period, these pocket gospels were seen as so protective that clans used them in battle as a talisman—known as a cathach or battle book—for victory.[22] One cathach in particular boasts an infamous history. The Cathach of St. Columba—also known as Colm Cille—was used in battle by the Donegal clan until the 11th century (fig. 9).[23] In fact, the sanctity of texts was regarded so highly that this book inspired a battle of its own prior to the clan’s ownership. St. Finnian lent the book to Colm Cille, who created an unauthorized copy of the text, which Colm Cille refused to give back to St. Finnian. A failed arbitration between the parties led to the battle of Cul Dremhne in 561 C.E.[24]

These pocket gospels required protection of their own in turn, in order to preserve the positive magic of God from the influence of evil.[25] Externally, the books were guarded by cumdachs. These satchels—or sometimes altars—had locks to protect from theft, as is evident from one of the only extant medieval satchels (fig. 10), which held the Book of Armagh. The satchel also exhibits the iconography already seen in the north high cross at Ahenny and the carpet pages from the Book of Durrow. The interlacing that brings to mind wattle fencing is likely the most associated with protection and containment. This type of hurdle was used to contain livestock and to demarcate land ownership or purposes, so it follows that it was also meant to serve as a containment or binding of the divine word to the pages of the book and to act as a deterrent to evil forces that might enter and corrupt it.[26] These weavings only bound the exterior flap of the satchel, but also portions of the Tara brooch (fig. 8) and the internal illuminations in many of the pocket gospels (fig. 1, 3 and 4).

Use of the book as a facilitator of experience

The book, as is suggested by the protective ornament, served as the incarnation of and access to the Christianized magic of the divine. Eleventh through twelfth century scholar and clergyman Hugh St. Victor cements this idea in his codification of principles around reading—developing prior to and during his time—when he writes,

The divine Wisdom, which the Father has uttered out of his heart, invisible in Itself, is recognized through creatures and in them. From this is most surely gathered how profound is the understanding to be sought in the Sacred Writings, in which we come through the word to a concept, through the concept to a thing, through the thing to its idea, and through its idea arrive at Truth.[27]

It is this divine truth manifested within and made accessible through Christian texts that held the purpose behind reading for early medieval monks in Ireland. Reading allowed clergy to seek, and potentially find, the supreme truth they sought through a prescribed process frequently referred to as the Lectio Divina and referred to in Hugh’s text on reading as the ‘four steps’ (which were, in fact, numbering five).[28] Hugh’s version of the Lection Divina follows this order: (1) study or reading for understanding; (2) meditation for counsel; (3) prayer to make petition; (4) performance, which is the process of seeking the truth; and, finally and nearly impossible to achieve, (5) contemplation upon the previous four steps for the finding of truth. The steps were theoretically succeeding, but required frequent regression to earlier steps to begin the process over in order to better achieve the step of finding divine truth.[29]

This process termed ‘reading’ has very little to do with reading as we now understand it, however. It was not a literal reading of the words on the page; instead, early medieval ‘reading’ represented a full-body reflective process embedded in the oral culture’s mentality that “you know what you can recall.”[30] This attitude results in religious books for a textual culture, books serving as a “written series of things readied for oral recall” to achieve intellectual and spiritual improvement.[31] It is also this attitude of textual culture that implies that the pages of the pocket gospels would likely have served more as cues for familiar, oft-visited memory paths than lines literally reread repeatedly.[32] The memory-focused approach allowed each recitation to follow the path of the Lectio Divina—a reader was not caught up in the process of reading, but in the process of reflection on the words being ‘read.’[33]

The idea of the book as a tools rather than as reading material actually fits comfortably within the progression of Western, Mediterranean-oriented culture both before and after the early medieval period. In the Roman tradition—as described by archaeologist Bettina Bergmann—memory training involved building an argument or recitation by building a mental home in which one travelled linearly past paintings depicting the argument as it proceeded.[34] Gospel books, thus, act as a physical manifestation of this guide in the early medieval period, whose Christian education long drew from Classical education and traditions.[35] The late medieval and early Renaissance periods also show a continuation of this progression in the form of books of hours, mentioned previously. These prayer books served to bring the reader closer to the truth contained within God’s word through the same meditative process seen in the Lectio Divina of the early medieval period, though for laypeople rather than for clergy.[36]

The experience facilitated by memorization and ‘reading’ in the Lectio Divina approach—as argued by both Hugh St. Victor and David B. Morris—promises not just spiritual health, but also bodily health.[37] During the early medieval period, a distinction was not drawn between the two; thus, to cure one’s spiritual ailments through the Lectio Divina process of accessing God’s healing truth, one also cures bodily ailments, thought to be manifestations of spiritual evil or weakness.[38] Hugh best phrases the dual benefits of Lectio Divina and the meditation encompassed within it when he writes,

[t]he start of learning, thus, lies in reading, but its consummation lies in meditation; which if any man will learn to love it very intimately and will despite to be engaged very upon it, renders his life pleasant indeed, and provides the greatest consolation to him in his trials. This especially it is which takes the soul away from the noise of earthly business and makes it have even in this life a kind of foretaste of the sweetness of the eternal quiet.[39]

Meditation removes the reader from the weaknesses of the body to return it to the perfection of God’s original creation. Once the reader returns to the material word after basking in the light of God’s truth, he is meant to return to his body, healed.

Conclusion

The book, in the form of pocket gospels in early medieval textual Ireland, served as an object of protection and as a means of accessing divinely blessed states of wellbeing. It is the culture of early medieval Ireland that allowed these functions to develop, thanks to the still fluctuating cultural relationship with literacy and non-Christian magic. Christian texts gained their power because they became bridges, a bridge between the Christian and non-Christian; a bridge between the oral and literate culture; and a bridge between divine power and humankind.

Figures

Bibliography

Bäuml, Franz H. “Varieties and Consequences of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy.” Speculum 55.2 (1980): 237-265.

Baxandall, Michael. “The Period Eye.” Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988.

Bergmann, Bettina. “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii.” The Art Bulletin 76.2 (1994): 225-256.

“Book of Durrow.” Pangur’s Bookshelf. 24 Aug. 2014.

“Cathach of St. Columba.” Encyclopedia of Irish and Celtic Art.

Cunningham, Lawrence S. and Keith J. Egan. Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition. New York: Paulist Press, 1996.

Cusack, Margaret Anne. “Mission of St. Palladius.” An Illustrated History of Ireland.

Flint, Valerie I. J. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991.

Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

“Hurdles & Fencing.” The Dorset Woodsman. 2016.

McGurk, Patrick. “Irish Pocket Gospel Book.” Sacris Erudiri 8 (1956): 249-269.

Morris, David B. “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 (Summer 2006): 539-561.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Stock, Brian. After Augustine: The Meditative Reader and The Text. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Stock, Brian. The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983.

Stock, Brian. Listening for The Text: On The Uses of The Past. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

Stocks, Bronwyn. “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours.” Word & Image 32.1 (2007): 16-24.

“The Cathach / The Psalter of St Columba.” Royal Irish Academy. 12 Sept. 2016.

Westwell, Chanry. “Put It In Your Pocket.” Medieval Manuscripts Blog. December 18, 2013.

Wiener, James. “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art.” Ancient History Et Cetera. 30 Oct. 2014.

Yvard, Catherine. “Pocket Books.” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[1] The period eye is a tool for scholars to construct—using contemporary documentation and evidence—the context and cultural signifiers of a time, enabling a fuller acknowledgement of and negotiating around modern biases and assumptions; Michael Baxandall, “The Period Eye,” Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988), 29-108.

[2] Baxandall, “The Period Eye,” 35.

[3] Stock investigates this idea throughout three of his books; Brian Stock, Listening for the Text: On The Uses of The Past (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990); Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983); and Brian Stock, After Augustine: The Meditative Reader and The Text, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

[4] In 431 C.E., Pope Celestine commissioned Palladius to mister to the Irish believing in Christ, suggesting that Christianity had established itself sufficiently to garner attention from the clergy in the decades before 430 C.E.; Margaret Anne Cusack, “Mission of St. Palladius,” An Illustrated History of Ireland.

[5] Stock, Listening for the Text, 142; Franz H. Bäuml, “Varieties and Consequences of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy,” Speculum 55.2 1980: 238.

[6] While the pocket gospel tradition remains strong through the early 12th century, I chose the period from 600-900 C.E. because the 600s marks the earliest known examples of this type of book and the 900s starts the period in which scribes began inserting additions and developing a more Anglo-Saxon style of illumination; Chanry Westwell, “Put It In Your Pocket,” Medieval Manuscripts Blog, December 18, 2013; Catherine Yvard, “Pocket Books,” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[7] Patrick McGurk, “The Irish Pocket Gospel Book,” Sacris Erudiri 8 1956: 250.

[8] Catherine Yvard, “Pocket Books,” Early Irish Manuscripts. December 16, 2015.

[9] Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World (New York: Routledge, 2002), 5-6.

[10] Stock, Implications of Literacy, 42.

[11] Ibid., 145.

[12] Ibid., 143-144.

[13] Ibid., 144.

[14] Ibid., 144.

[15] David B. Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 2006: 551.

[16] Bronwyn Stocks, “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours,” Word & Image 32.1 2007: 16.

[17] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 256.

[18] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 4 and 254-257.

[19] Valerie I. J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), 260-261.

[20] James Wiener, “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art,” Ancient History Et Cetera, 30 Oct. 2014.

[21] “Book of Durrow,” Pangur’s Bookshelf, 24 Aug. 2014.

[22] “Cathach of St. Columba,” Encyclopedia of Irish and Celtic Art.

[23] “The Cathach / The Psalter of St Columba,” Royal Irish Academy, 12 Sept. 2016.

[24] Ibid.

[25] James Wiener, “Ireland’s Exquisite Insular Art,” Ancient History Et Cetera, 30 Oct. 2014.

[26] “Hurdles & Fencing,” The Dorset Woodsman, 2016.

[27] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, trans. Jerome Taylor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 122.

[28] Originating in the writings of Saint Benedict in the 6th century, Lectio Divina traditionally proceeded through a fourfold process: (1) reading; (2) meditation; (3) prayer; and (4) contemplation. Lawrence S. Cunningham and Keith J. Egan, Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition (New York: Paulist Press, 1996), 38.

[29] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, 132-133.

[30] Ibid., 93-94; David B. Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” New Literary History 37.3 2006: 542; Ong, Orality and Literacy, 3.

[31] Ong, Orality and Literacy, 121.

[32] Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” 551.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Bettina Bergmann, “The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii.” The Art Bulletin 76.2 1994: 225.

[35] Stock, Implication of Literacy, 16.

[36] Stocks, “Text, Image, and A Sequential ‘Sacra Conversazione’ in Early Italian Books of Hours”: 16.

[37] Morris, “Reading Is Always Biocultural,” 551.

[38] Ibid., 551-552.

[39] Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, 92-93.

N.B. All images reproduced under the principle of Fair Use.

]]>The Qianlong porcelain plate, accession number 2011.19 at the Ackland Museum, represents the intersection of artistic, economic, and social interactions between Europe and China in the mid-eighteenth century.[1] Upon initial examination, I thought that 2011.19 might serve as an example of art mediating a colonial relationship. Further research, however, revealed that the plate is a confluence of the artistic and economic interactions between East and West, not representative of a colonizing relationship. The Qianlong government denied foreigners all but the most limited economic exchanges with their country, and the plate decoration announces that Chinese artisans adopted popular Western styles to increase sales, appealing to Westerners’ growing obsession with the exotic. Analyzing an object for which social, political and economic context is key to its understanding and interpretation demands a social art historical approach.[2] 2011.19 fits ideally within the examination of methods of production and power dynamics key to the New Art History.

Made circa 1745, this high fire porcelain plate—with low fire polychromatic enamel decoration—depicts both the heraldic crest and coat of arms for Admiral Sir Francis Holburne, as well as three harbor views known well by British naval officers travelling between Britain, India and China.[3] During the mid-eighteenth century, the Qianlong government maintained strict control of their land, making Canton (now Guanzhou) the only port city in China accessible, in part, to Westerners. Foreigners weren’t permitted to leave the small quarter of the city granted to their trading companies and endured complicated and inconsistent levies against their imports and exports.[4]

Despite these restrictions, the artistic practices of both cultures influenced one another significantly, though with different audiences and for different reasons. The Chinese artisans decorating the plates and designing the forms were interested in the changing fashions of Western visual culture so to better serve their customers and to speed up production. As Andrew Madsen and Carolyn White point out in their comprehensive introduction to the practice and history of Chinese export porcelain, if a particular pattern became popular, Chinese artisans would create a surplus to fill orders for the next season.[5] I argue that this practice possibly explains why the waterscapes painted on Admiral Holburne’s service exactly match that of both Lord Anson and of Sir George Cooke.[6] Though Holburne was a naval officer during the heyday of the British East India Company, he sailed West—remaining in the waters near England or sailing to the West Indies or Canada—rather than East, the course that would have resulted in his familiarity with the scenes depicted on this plate.[7] Though he likely would have known Plymouth Sound on the southern coast of England, he perhaps never himself witnessed the Whampoa anchorage near Canton, nor Fort St. George in Madras, both of which compose the major anchorages on the journey between England and China.[8] Holburne’s order of a service depicting the rush East reconfirms just how fashionable it was to show off knowledge of or connections to these popular, exotic places.

Chinese artisans regularly displayed knowledge of Western stylistic developments and visual interests stemming from the new British middle class’ growing thirst for items displaying an exotic aesthetic. Plate 2011.19 provides the ideal case study for the display of this awareness. Thomas Litzenburg breaks down the major content themes of British interest into seven categories, three of which are contained in the plate’s decoration: (1) Armorials, (2) Topographical and Architectural Views, and (3) Marine Subjects.[9] Armorials exploded in popularity from the end of the seventeenth century until the end of the eighteenth. Chinese painters honed their copying skills from gaming counters, bookplates, painters’ books for coach doors, other ceramics, and paintings, engravings or sketches of the family coat of arms provided by the merchants placing the order.[10] The sheer volume of connections traced back to and from export porcelain—enumerated in David S Howard’s text on armorial porcelains—makes apparent how important these services were in displaying the socio-economic weight of these delicate items, which will be further discussed below regarding Chinese artistic influence on the West.[11] The changing tastes in ceramic border styles were also of interest to the Chinese artisans. Though Holburne might have ordered the Meissen-style cartouches and quatrefoil center panel specifically after becoming familiar with them during his time sailing the North Sea in 1740, I’m inclined to assume that Meissen borders were simply the most popular style of the time and thus came standard with the set that was pre-painted in readiness for a rush of orders, since several other services exist with the same scenes framed by identical cartouches and quatrefoil.[12]

While a more formal art history and connoisseurship were used to discover the connection between these visual sources and their porcelain counterparts, this network of art references hold relevance to a social history of art, clarifying Western motivations in selecting Chinese porcelain. While China showed determination in remaining current on Western styles purely for economic gain and to dominate the market, European gentry and the fledgling middle class displayed an energetic interest in incorporating chinoiserie into their material lives as an assertion of the value of their socio-economic status. The choice to commission porcelain from China rather than the slightly less consistent Western porcelain companies emphasizes Britain’s growing obsession with the exotic. Respectability remained bound up in the pairing of decorum with its coordinating material goods.[13] Since the fledgling middle class of the Enlightenment sought the status of the gentry, they ordered Chinese porcelain to serve as the material evidence of their elevated social status. It is my opinion that the landed gentry responded to this threat by reinvigorating their own commissioning of Chinese export items, as evidenced by the steep increase in armorial porcelain dinner services. Armorial porcelain with depictions of foreign travel through topographical and architectural views, as well as marine subjects, served as the upper class’ proof that they not only had knowledge of the exotic market, but also maintained high-class taste.[14] The scenes from Holburne’s service reinforce this idea. Each scene is drawn from a fantasy of exotic travel and famous images drawn from that travel, and all of them are identical to the service of the famous Lord Anson, who was Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty, a member of British Parliament, and a circumnavigator the globe.[15] Particularly due to Lord Anson’s poor opinion of Holburne, it seems likely that Admiral Holburne would hope to benefit his own position by flattering a man of such social power in Britain not known to favour him.[16] Thus Holburne not only reinforces his personal connection to the landed gentry through the inclusion of his crest and coat of arms, he also restates his socio-political status by displaying the same harbor scenes on the service owned by Lord Anson himself.

Plate 2011.19, through the lens of social art history, becomes an embodiment of the social, political and economic factors at play in the East-West trade of material good and artistic styles. Chinese artisans benefited economically from the use of Western imagery while the upper and middle classes of Europe, particularly Britain, used export items as an expression of social power and as a political tool. Without the social art historical approach, the evidential value of the contents of the plate would be lost to more pure stylistic analysis and connoisseurship.

Bibliography

D’Alleva, Anne. Methods & Theories of Art History. London: Lawrence King Publishing, 2012.

Howard, David Sanctuary and John Ayers. China for the West: Chinese Porcelain & Other Decorative Arts for Export Illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection. London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978.

Howard, David Sanctuary. Chinese Armorial Porcelain. Chippenham, UK: Heirloom & Howard Limited, 2003.

Kerr, Rose. Chinese Ceramics: Porcelain of the Qing Dynasty 1644-1911. London: V & A Publishing, 1986.

Kerr, Rose and Luisa E. Mengoni. Chinese Export Ceramics. London: V & A Publishing, 2011.

Laughton, J. K. “Holburne, Francis (1704–1771).” Rev. Ruddock Mackay. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed., edited by Lawrence Goldman, January 2008.

Litzenburg, Thomas V. Chinese Export Porcelain: in the Reeves Center Collection at Washington and Lee University. London: Third Millennium Publishing, 2003.

Madsen, Andrew D., and Carolyn L. White. Chinese Export Porcelains. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2011.

Perdue, Peter C. “Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System: Canton & Hong Kong.” MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2009.

Riggs, Timothy. Curatorial notes for accession number 2011.19. Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill, NC. 17 November 2015.[17]

[1] Timothy Riggs, curatorial notes for accession number 2011.19, Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill, NC, 17 November 2015.

[2] Anne D’Alleva, Methods & Theories of Art History (London: Lawrence King Publishing, 2012), 53-4.

[3] Rose Kerr, Chinese Ceramics: Porcelain of the Qing Dynasty 1644-1911 (London: V & A Publishing, 1986), 51; David Sanctuary Howard and John Ayers, China for the West: Chinese Porcelain & Other Decorative Arts for Export Illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978), 201; Thomas V Litzenburg, Chinese Export Porcelain: in the Reeves Center Collection at Washington and Lee University (London: Third Millennium Publishing, 2003), 102.

[4] Peter C Perdue, “Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System: Canton & Hong Kong,” MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2009; Rose Kerr and Luisa E. Mengoni, Chinese Export Ceramics (London: V & A Publishing, 2011), 17.

[5] Andrew D Madsen and Carolyn L White, Chinese Export Porcelains (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2011), 44.

[6] For images of Cooke’s service, see Litzenburg, Chinese Export Porcelain,

[7] J.K. Laughton, “Holburne, Francis (1704–1771),” Rev. Ruddock Mackay, In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford: OUP, 2004).

[8] The Plymouth Sound composite scene is on the left side of the lip. The Whampoa anchorage is located on the right. The Madras anchorage is in the center of the well.

[9] The other four categories are (1) Literary & Historical Subjects, (2) Mythological, Religious & Masonic Subjects, (3) Figure Models, and (4) Western Forms & Decorations; Litzenburg, Chinese Export Porcelain, 37-9.

[10] David Sanctuary Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain (Chippenham, UK: Heirloom & Howard Limited, 2003), 33-48.

[11] Ibid., 30-49.

[12] Litzenburg notes that at least ten other armorial services are known to bear the same decoration with the Meissen-style border cartouches and quatrefoil panel, Litzenburg, Chinese Export Porcelain, 102; see the service bearing the arms of Sir George Cook, as pictured in Litzenburg, Chinese Export Porcelain, 103.

[13] Andrew D Madsen and Carolyn L White. Chinese Export Porcelains, (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2011), 18.

[14] Ibid.

[15] The Plymouth Sound, Madras and Whampoa scenes are all drawn from engravings made by well-known artists at the time, again restating the assertion of power built into the imagery of these plates; not only do these upper-class commissioners have first hand experience with these new, exciting places, they also have the taste to identify and incorporate the best of their visual culture. In fact, not only did Anson know of one of the artists, Piercy Brett, Anson also requested Brett’s presence on his circumnavigation of the globe, thus proving himself the driving force behind the public’s access to views of the wider world; David Sanctuary Howard and John Ayers, China for the West: Chinese Porcelain & Other Decorative Arts for Export Illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978), 202-04.

[16] Laughton, “Holburne, Francis (1704–1771).”

[17] Debate surrounds the citation for curatorial notes. This is what the Chicago manual of Style Online suggests for curator’s statements, so I felt that this version is the most authoritative. An alternate form of citation is as follows: Riggs, Timothy. Curatorial notes for accession number 2011.19. Chapel Hill, NC: Ackland Art Museum. 17 November 2015.

]]>