The Harry Ransom Center recently launched a digitization project entitled Project REVEAL (Read and View English and American Literature). As an institution with astounding resources available to them, the Center had the luxury of approaching the project as a model of ideal digitization workflows for future scanning endeavors both in-house and in the wider community. Part of Project REVEAL’s objective was to scan twenty-five of the HRC’s English & American author collections in a way that respects original order and disregards the traditional approach of only digitizing collection highlights. Going box by box, folder by folder, and item by item, the project digitized and provided detailed metadata at the most granular level.

Most organizations, however, do not have the time, finances, nor support to accomplish such a dedicated attempt at digitizing their collections. Collections may not be processed to the item level. Oversized or delicate items may require more specialized handling and scanning than the facility can accommodate. The money supporting the digitization may only stretch far enough to allow the scanning of collection highlights.

To experiment with just how long a high quality scan can take, I digitized a proofing press run of a block from Wellesley College’s Book Arts Lab collection on my HP Photosmart C4700 flatbed scanner. The 3×4 inch scrap of card, scanned at 4800 dpi, took 1 minute to scan and save. While my flatbed is aged and amateurish compared to newer, professional grade scanners, items scanned at a high enough dpi to withstand being resized and to accommodate zooming features takes a marked amount of time, which increases many times over when digitizing larger items. Then there’s the concern of file size and type. I used a .jpeg format, since my purposes don’t require an uncompressed, high quality .tiff. But any archival purposes would require that caliber of format. The opening and downloading of higher quality files is its own time commitment and can severely slow down the loading of the image or the webpage in which it’s embedded, even though the excellence of the scanned image is worth the wait.

While these considerations might discourage most organizations from keeping up with the standards the HRC laid out in Project REVEAL, the project’s imaging and metadata standards. And they don’t differ much from the standards laid out by the Library of Congress, FADGI or Besser’s recommendations. Without a quality image available for easy, detailed viewing (and potentially for download), a digitization project loses all significance.

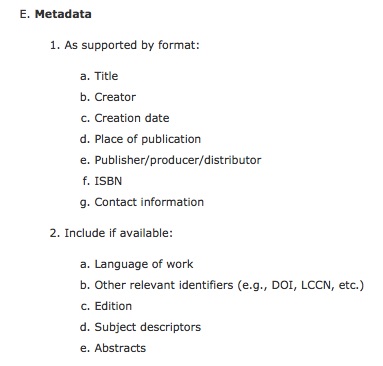

These quality images don’t mean much without their metadata, though. Current technology remains incapable of auto populating metadata fields better than a human viewer. [1] Consequently, to compare or search image files, one needs sufficiently descriptive metadata. Project REVEAL, under ‘Object Description,’ includes the fields Title, Creator, Date, Description, Subject (includes medium and format details), Subject, Language, Format, Extent (eg number of manuscript pages), Digital Object Type, Physical Collection, Collection Area, Digital Collection, Repository, Rights, Call Number, Series, Identifier, Finding Aid and File Name. For description of the image, rather than the object, Project REVEAL includes the categories of Title and File Name. The metadata sections also provide menus for Tags and Comments, which allows for user participation in making the object even more relevant to viewers. As an archival institution, the HRC emphasizes metadata representative of their storage structure, such as collections and series identifiers. While HRC modified their metadata structure for their purposes, the Library of Congress lays out general guidelines for digital material metadata that follows similar lines:

More information on metadata standard will come in a later post.

Digitization standards hold relevance beyond the institutional level, too. Individuals establishing an archive—such as visual artists, writers or genealogists—also require workflows for the digitization of their materials. While both Introduction to Imaging and “Becoming Digital” are oriented towards organizations, their suggestions can be instructive for project planning at an at-home level. When looking to digitize personal materials, the highest quality images might not be necessary (especially since materials at the highest resolution take quite a while on at-home scanners, as illustrated by my own experimentation). But Introduction to Imaging‘s chapter on “The Image” is supremely instructive in identifying what an individual might require for their digitized images to serve their needs. The subsections on Bit Depth, Resolution and File Format illustrate what one will get out of using various levels of depth, size and compression. By literally illustrating the limits and advantages of each aspect of the scanning process, Besser saves individuals’ time and storage by allowing them to see what those images can do at each level—one need not reinvent the wheel in taking the time to experiment with all of the combinations of aspects personally.

For those working in text-heavy digitized objects, OCR (Optical Character Recognition) might be an avenue to consider before setting off on a digitization project. Unfortunately, even neatly written handwritten materials don’t respond well to OCR programs, nor do items with variable formatting and fonts (like newspapers or mathematical treatises). But if your materials are type written—such as manuscripts produced on a typewriter—OCR might be an avenue to explore. “Becoming Digital” explains the OCR evaluation process quite well, including a breakdown of programs’ efficacy and price point, in its chapter on “How to Make Text Digital.” Impact’s Tools & Resources page on Tools for Text Digitization provides an even more in depth breakdown of the options out there, though it does not provide pricing information.

While I can see the appeal of OCR for a larger typewritten collection that needs to be searchable down to the phrase, it seems less useful in virtually any other context, since price for software, time for processing and effort for verification/correction result in an imbalance between energy input and product output. An answer to the instinct to OCR materials might instead to be thoroughly descriptive in the metadata fields of Description, Subject and Tags.

For more examples of digitization projects, take a look at sites like the Digitization Projects Registry to see how various organizations are implementing these technical suggestions.

[1] MIT recently developed a program that could recognize if a painting was in the style of cubism, but it’s far less expensive to have a practiced eye tell you that in the same amount of time than ask a computer to run the program, which isn’t equipped to identify every object, style or variation therein.

Instructional Resources for Digitization:

- Howard Besser, ed. Sally Hubbard with Deborah Lenert. Introduction to Imaging. Getty Research Institute Publications, Revised 2003. http://www.getty.edu/research/publications/electronic_publications/introimages/index.html

- Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig. “Becoming Digital.” Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web, 2006. http://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/digitizing/

- FADGI (Federal Agencies Digitization Guidelines Initiative). http://www.digitizationguidelines.gov/

- IMPACT (Improving Access to Text). http://www.digitisation.eu/training/recommendations-for-digitisation-projects/

- Library of Congress, Recommended Format Specifications. http://www.loc.gov/preservation/resources/rfs/TOC.html